Haiti: Caracol Industrial Park

-

Overview

With support from Accountability Counsel and local partners, the Kolektif Peyizan Viktim Tè Chabè (the Kolektif), a collective of Haitian farmers and their families – representing nearly 4,000 people – displaced by the Caracol Industrial Park, negotiated a historic agreement with the Inter-American Development Bank and the Haitian government to restore their livelihoods.

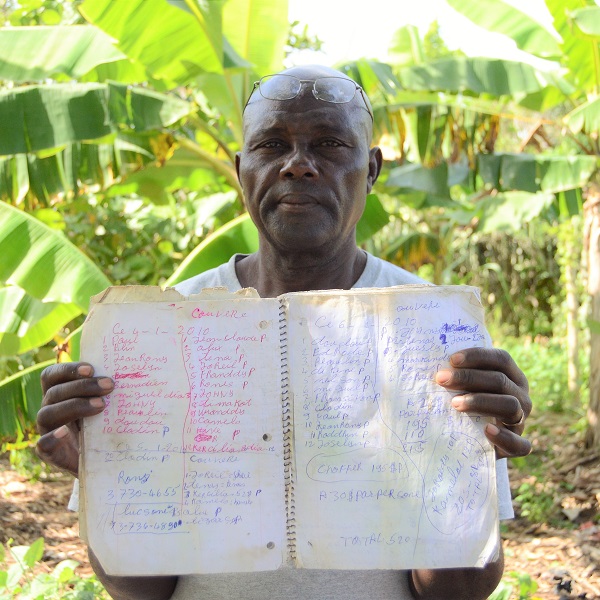

Elie Josué holds a ledger of the seasonal workers he employed on his plot (ActionAid/Marilia Leti)

In 2011, hundreds of Haitian farmers and their families lost their livelihoods when they were forced off their land to make way for the large industrial facility in northeast Haiti. On 12 January 2017, the seventh anniversary of the earthquake, the Kolektif filed a complaint to the Independent Consultation and Investigation Mechanism (MICI) of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) to demand accountability and remedy for the bank’s role in their displacement and the severe harm it caused to their families.

The complaint initiated a year-long negotiation process between the Kolektif and their advocates, representatives of the IDB, and representatives of the Haitian government with facilitation by MICI. This process included information sharing about impacts of the Industrial Park, and detailed, technical surveys to capture the losses of farmers and their families. On December 8, 2018, the parties reached an historic agreement that provides for remedial support with a combination of land, employment opportunities, agricultural equipment and training, and support for micro-enterprise focused on women and the most vulnerable members of the community.

This negotiation process serves as a model for communities around the world who are working to address deep power imbalances and harm from international investment through dispute resolution.

“I’ve farmed my land for 21 years and was then forced to leave for the construction of this park. I grew black beans, cassava, corn, peanuts and bananas on my land and raise all of my children because of that land. I would hire 100 seasonal workers during our planting seasons. I paid them 150 gourdes a day and two meals. If we had the support we needed to farm our land, we would be doing well. Now that I’ve lost my land, I don’t have a penny.” — Elie Josué, pictured above, had a plot of 4.5 hectares and exported his produce throughout Haiti

-

The Story

In January 2011, more than 420 farmers and their families who survived the 2010 Haitian earthquake were forcibly displaced, almost overnight, losing their land to the Caracol Industrial Park (CIP) and leaving them in a state of financial and food insecurity.

In January 2011, more than 420 farmers and their families who survived the 2010 Haitian earthquake were forcibly displaced, almost overnight, losing their land to the Caracol Industrial Park (CIP) and leaving them in a state of financial and food insecurity.The CIP, an export-oriented industrial park pitched as post-earthquake aid, was constructed on 250 hectares of the most fertile agricultural land in the area. The produce cultivated on that land provided the primary source of income, as well as crucial food, to those farmers and their families, some of whom had farmed the land for generations. The land also supported cattle, another important source of income and nutrition. Those families were displaced from their land with no more than a few days’ notice.

Although compensation was eventually provided to most families, it was poorly consulted, delayed, and ultimately inadequate to rehabilitate the families’ livelihoods. The vast majority of the farmers are now in a worse socioeconomic position than before they were displaced and are struggling to meet their basic needs.

The families are also concerned about the ongoing lack of information and consultation about the cumulative environmental and social impacts of the CIP on their communities and on their natural resources, including the sensitive coastal mangrove and coral reef ecosystem in Caracol Bay and the Trou du-Nord River. There are also reports of persistent labor code violations at the CIP and strained public resources exacerbated by the influx of CIP workers.

The CIP has received significant international financial support from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), among others, as part of earthquake reconstruction efforts. Accountability Counsel, together with partner organizations including the ActionAid federation, is supporting the Kolektif to raise their concerns with the IDB and other stakeholders.

“We had land that we had either received from our parents or that we had bought. With that land we could live. It represented all the little details that we need to live. … Land represented life for us. The little money they gave us was gone in one month, two months.” — Jocelyn Prévil, who lost land and who now coordinates the representatives of the Kolektif

On the seventh anniversary of Haiti’s devastating earthquake, the Kolektif Peyizan Viktim Tè Chabè (the Kolektif), assisted by Accountability Counsel and local and international partners, filed a complaint to the IDB’s Independent Consultation and Investigation Mechanism (MICI). The complaint seeks fair compensation for the IDB-funded land grab, as well as meaningful consultation regarding the project’s social and environmental risks and steps taken to manage negative impacts.

The Kolektif Peyizan Viktim Tè Chabè is a collective of families who were displaced from the land they cultivated in Chabert for decades to make way for the Caracol Industrial Park (CIP), financed by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), in Northeast Haiti. The land taken for the park was the most fertile agricultural land in the area. Almost overnight, the farmers and their families lost their primary source of income and food security. They waited almost three years for promised replacement land, only to be told that most families would instead receive an inferior and inadequate cash compensation package. Almost all of those families now struggle to meet their basic needs.

In this video, one of our partner organizations, ActionAid USA, shows the reality of the CIP, including the displacement of Haitian farmers and the poor employment conditions within the park.

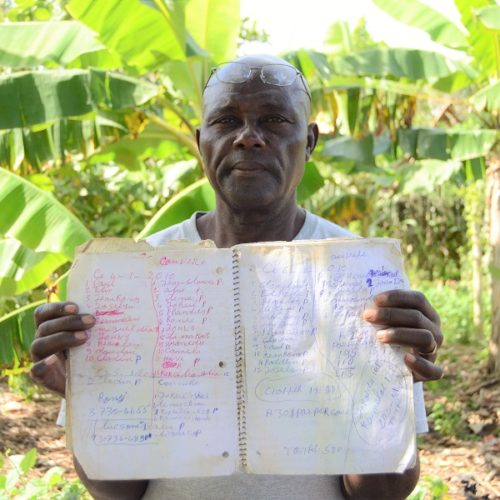

Etienne Robert is a 72-year-old father of four.

He owned a plot of land that was divided in half by the walls of the CIP

(ActionAid/Marilia Leti)History

In the rush to begin the project, the CIP site was chosen without analysis of the project’s environmental and social impacts, including how it would impact the hundreds of farmers cultivating that land. The pre-feasibility assessment for the CIP, funded by the IDB, wrongly described the chosen site as “devoid of habitation and intensive cultivation.” In fact, the CIP site was the most fertile land in the area, cultivated in plots by more than 420 farmers and their families, totaling nearly 4,000 people.

In January 2011, those farmers and their families were displaced from their land, with no more than five days’ notice. Some had no notice at all. Almost overnight, they lost a vital source of income and food security. This displacement violated the IDB’s Involuntary Resettlement Policy, which requires the Bank to conduct due diligence and meaningful consultation and to prepare a Resettlement Action Plan (RAP), all before displacement occurs.

After displacement occurred, the IDB and its client, the Technical Execution Unit (UTE) of the Haitian Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF), attempted, belatedly, to satisfy key environmental and social standards, including resettlement obligations. The IDB initially promised to provide families with replacement land but later reneged on that promise. The alternative land in Terrier Rouge, identified by UTE, was in fact being cultivated by other communities. Those farmers were willing to share the land, but only under conditions that were deemed too expensive.

“… The ground of the chosen site is the most fertile in the whole area, even in dry periods. It is also the source of income for many occupants who have no other activity than cultivating this land. Entire families depend on these plots to feed their children and pay school fees, health care costs and reimburse debts. … Culturally, some families have occupied this land for several generations. These occupants have developed natural ties with the land, some nutrition habits. Almost every day and all year long, they draw leaves or vegetables that contribute to their diet.” — The results of community consultation, conducted only after the land was taken, as recorded by the project’s Environmental and Social Impact Assessment

Marie Marthe Rocksaint (Photo credit: Marilia Leti/ActionAid)

In the end, after waiting almost three years for replacement land, most families were forced to accept an inferior lump sum cash payment that has proved insufficient to restore their livelihoods. Six years after their displacement, some families are still waiting for their compensation. During this period, the area in and around Caracol has experienced sharp increase in the cost of living and demand for food, shelter, and land, which has further reduced the value of the compensation.

The IDB and UTE also failed to properly investigate and mitigate different and disproportionate impacts on women. Women, including female children, are likely to have been disproportionately impacted by inadequacies of the compensation and rehabilitation packages.

Almost inevitably, given the inadequate due diligence, the delays, and the broken promises, the compensation packages failed to restore the standard of living of those displaced.

“I had farmed my land for 22 years, but was made to leave without any compensation. Afterwards, the government sent investigators who were asking for all kinds of information from us but they never told us how much compensation they were going to give us. There were no negotiations, we were told to accept the compensation that they were going to give us. We thought the park was going to benefit us. First they promised us land, then housing, then all we got was a small amount of compensation.” — Marie Marthe Rocksaint, pictured above, a smallholder farmer and mother of two

Loudrigeka’s father lost his land at the CIP site. He now cannot afford her school fees

and fears for her future.The vast majority of the people affected by the project report that they are in a worse socioeconomic position than prior to displacement, facing financial and food insecurity. Of the 58 heads of affected families the Kolektif interviewed in May 2016, they found that:

- 54 people report that they are now in an unstable economic situation, with 48 being forced to incur debts regularly

- 46 people report being in a worse situation than before they lost their land, 11 said their situation is neither better nor worse, and only one said to be in a better situation

- Four said they have not received all the compensation reported in the compensation agreements, and two said they have received no compensation at all

- The children of eight victims migrated to the Dominican Republic due to a lack of economic opportunities. Others report that the decline in income and the delays in receiving compensation prevented families from financing their children’s education

- The victims mainly used their financial compensation for immediate and unavoidable expenses that they had previously paid with the cash they obtained from their land: food (49), school fees (47), and debt repayment (37)

- For a majority, their revenues today come from agricultural activity (growing crops or livestock) on lower quality land they lease or that they owned in other areas, or as agricultural workers (33). Eleven generate revenues by selling coal, ten through small businesses, five by harvesting salt, three as masons, three as fisherfolk

- None of the victims interviewed had access to transitional livelihoods training and only one reports that a family member received a training, and

- Six report having no source of income at all following their displacement.

The members of the Kolektif are also concerned by the ongoing lack of information and consultation about the cumulative environmental and social impacts of the CIP on their communities and the area’s biodiversity and natural resources. The park is located approximately four kilometers inland from Caracol Bay, a sensitive coastal mangrove, sea grass and coral reef ecosystem that is home to endangered plants and species, as well as important community resources, such as salt basins, fish and shellfish. The Trou-du-Nord River, which flows into Caracol Bay, runs through the site chosen for the Caracol Industrial Park. The park discharges wastewater into this river, putting both the river and bay at risk from chemicals and other pollutants. There are also reports of persistent labor code violations at the CIP and strained public resources due to the influx of CIP workers.

Despite the growing, and now long-standing evidence of the inadequate management of negative environmental and social risks and impacts caused by the CIP, the IDB has continued to fund and expand the project at regular intervals. It seems that there was no going back, despite the growing financial, environmental and social cost.

Initial Steps

After waiting years for promised replacement land, victims of the CIP land grab organized themselves into the Kolektif. Working with ActionAid Haiti, Accountability Counsel and other partner organizations, the Kolektif has made many attempts to document and raise their concerns with IDB and UTE, in an effort to constructively resolve the issues.

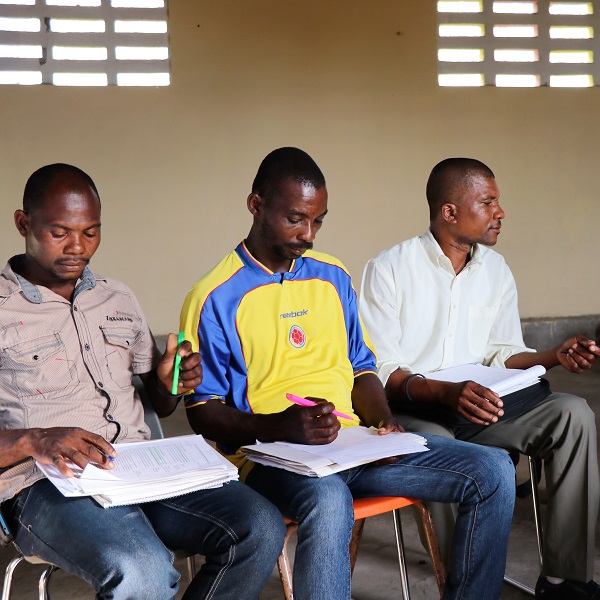

Representatives of the Kolektif participate in a training session with Accountability Counsel

The Complaint

As the Kolektif’s primary concern is the harm associated with displacement, the complaint is focused on these issues. The complaint explains that the families were harmed by the following IDB policy violations:

- The families were displaced without safeguards;

- The CIP site was selected without the thorough alternatives analysis that would have minimized the impact on those families;

- The Bank and its client failed to collect adequate and accurate information about the families and their losses;

- The Bank failed to consider and to mitigate gender-specific risks;

- The required assessment of the risk that families could be left further impoverished was inadequate and inconsistent;

- The Bank’s client failed to secure replacement land prior to displacement;

- The families were not meaningfully consulted;

- Compensation was not timely, fair, or adequate; and

- The Bank failed to monitor and evaluate the process in a timely manner.

Despite the harm suffered to date, the Kolektif believed that fair compensation and rehabilitation, in fulfillment of IDB’s obligations, remained possible through constructive dialogue addressing the following solutions:

- Fair financial compensation;

- A compensation verification and complaint mechanism;

- Revision of the vulnerable people criteria and list;

- Fair non-financial compensation to rehabilitate livelihoods;

- Support to victims’ families’ education projects.

Additionally, the Kolektif requested a new, meaningful, consultation process, explaining the current environmental and social risks and impacts and facilitating the affected communities’ input into how those will be managed.

Representatives of the Kolektif meet with MICI and the dialogue facilitator

The Dialogue

As a result of the complaint, MICI initiated a negotiation process between the Kolektif and their advocates, representatives of the IDB, and representatives of the Haitian government with facilitation by the accountability office. The 18 month-long process included information sharing about impacts of the Industrial Park, and detailed, technical surveys to capture the losses of farmers and their families.

On 8 December 2018, the parties reached an historic, negotiated agreement that provides for remedial support with a combination of land, employment opportunities, agricultural equipment and training, and support for micro-enterprise focused on women and the most vulnerable members of the community.

The implementation process that comes next will be the test of the power of the agreement and the commitment of the parties. Accountability Counsel will continue to support the Kolektif’ to ensure that the commitments made in the agreement are met.

Case Partners

ActionAid Haiti: The local affiliate of ActionAid, a global movement of people working together to further human rights and defeat poverty.

Kolektif Peyizan Viktim Tè Chabè: A collective of victim families who were displaced from their agricultural land in Chabert to make way for the Caracol Industrial Park.

AREDE (Action pour la Reforestation et la Défense de l’Environnement): A nongovernmental community-based organization that advocates on environmental and social issues affecting Northern Haiti.

-

The Case

-

Dec 2018

The parties reached a final agreement to resolve the Kolektif’s complaint regarding the taking of their farmland for the Caracol Industrial Park. A summary of the agreement is available in English, French & Creole. See also MICI’s Consultation Phase Report.

-

Jun 2017

The Independent Consultation and Investigation Mechanism (MICI) of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) completed its assessment, concluding that a facilitated dialogue process was viable and should be initiated, after the IDB agreed to participate in that process together with representatives of the Kolektif Peyizan Viktim Tè Chabè (Kolektif) and of the Haitian government.

-

Mar 2017

MICI concluded that the Kolektif’s complaint was eligible and began an assessment of whether dispute resolution would be possible. The eligibility decision is available in English, French, and Creole.

-

Feb 2017

IDB Management submitted a formal response to the complaint, available in English, French, and Creole. While it acknowledged that the environmental and social risk management for this project has been challenging, the response minimizes the Kolektif’s concerns and attempts to limit the scope of the complaint process.

-

Jan 2017

MICI registered the complaint.

-

Jan 2017

On the seventh anniversary of Haiti’s devastating earthquake, the Kolektif, assisted by Accountability Counsel and local and international partners, filed a complaint to the MICI: available in English and in Creole. The Kolektif asserts that their land was taken from them without adequate notice, consultation or compensation, to make way for the Caracol Industrial Park (CIP) project, and that its members continue to suffer significant harm as a result. The Kolektif also raises concerns about broader environmental and social impacts the construction and operation of the CIP and connected facilities could cause to the surrounding communities and the area’s rich biodiversity. The complaint includes a series of annexes with additional information and documentation.

-

May 2016

After some delay, a meeting was held in May 2016. However, despite an apparently constructive tone during that meeting, the IDB and UTE were slow to respond to further contact and appeared dismissive of the Kolektif’s concerns. In a particularly disparaging response, UTE suggested that a July 10, 2016 letter from the Kolektif was signed only by “troublemaking” civil society organizations, not people affected by the CIP.

-

Apr 2016

On 3 April, 2016, 225 members of the Kolektif signed a letter to UTE Director, Mikael de Landsheer, and IDB Director in Haiti, Mr. Gilles Damais, explaining their concerns and requesting further information. The Kolektif also requested a meeting to discuss the concerns further.

-

Jan 2015

ActionAid published a report on the displacement of 366 families to make way for the CIP.

-

Oct 2013

The Worker Rights Consortium published a report discussing the pervasive wage violations in Haiti’s apparel industry, including violations at the CIP.

-

Jan 2013

Gender Action published a report assessing how the World Bank and IDB took into account (or, rather, did not take into account) the needs of Haitian women in post-earthquake development projects.

-

Jan 2013

Gender Action published a report on the gender-specific impacts of the CIP in its first year of operation.

-

Jul 2011

An initial loan of $55 million was approved by the IDB Board of Directors on 25 July, 2011. The IDB has financed the CIP from its earliest stages, and has continued to invest in the project through five loans totaling approximately $242 million and through more than a dozen technical cooperation projects.

-

Jan 2010

In 2010, Haiti suffered a severe earthquake that had devastating effects on the capital, Port-au-Prince. As part of the effort to rebuild the country, a proposal to construct a large export-oriented industrial park in Northern Haiti – which would become the CIP – was fast-tracked in an attempt to decentralize the country’s economic and social infrastructure away from Port-au-Prince and produce export-based economic benefits.

-

-

Impact

Members of the Komite, during a training session with Accountability Counsel attorneys

The Kolektif, through its leaders, the Komite, and its partners at ActionAid Haiti, sought specific help from Accountability Counsel to develop and pursue a complaint to the IDB’s accountability office, MICI. In particular, they sought assistance to establish a facilitated dialogue process between the Kolektif, the IDB, and the Haitian Government to discuss specific solutions to the harms their communities were suffering. Accountability Counsel worked with the Komite to gather additional information and to develop and present a detailed complaint to MICI, which was filed on 12 January 2017. Since then, Accountability Counsel attorneys have provided regular support to the Komite and its local and national partners throughout the complaint process. This support has included multiple trips to Haiti to conduct trainings, gather relevant information, and accompany the Kolektif during MICI site visits.

Accountability Counsel helped the Komite achieve their first, major milestone of the complaint process: the establishment of a historic dialogue process between the Kolektif, the IDB, and the Haitian Government. Accountability Counsel provided remote and in-person support throughout this process as the Komite sought solutions to both better the lives of over 450 displaced families and provide lessons for avoiding similar harm to communities in the future.

After a year of negotiations, the parties reached an historic agreement on 8 December 2018. The agreement provides for remedial support with a combination of land, employment opportunities, agricultural equipment and training, and support for micro-enterprise focused on women and the most vulnerable members of the community. This negotiation serves as a model for communities around the world who are working to address deep power imbalances and harm from international investment.

This agreement marks an incredible step forward for the farmers, but its ultimate impact will require strong multi-party oversight. Accountability Counsel will continue to support the Kolektif’s leaders through this critical phase to ensure that the commitments made in the agreements are met.

“I’m so happy that Accountability Counsel and AREDE have given all of themselves to support us and to help us in our fight. Thanks to them, now we’ve come to a point where we can see the end at hand. And we need to make sure that we fulfill the wishes of the more than 400 families who chose us to represent them. Because like they showed us, when people choose you to support them, you’re like their lawyer, and you have to defend them and their rights no matter what, so we’re going to do that for them too.” – Seliana Marcelus, a member of the Komite, whose father lost land, and who is now seeking fair compensation for all of the displaced families

-

Case Media

Fact Sheets

Videos

Media Coverage

- 15 June 2022 These Haitians Were Children When A US-Funded Project Evicted Them From Their Land. They Can’t Afford College. By Karla Zabludovsky

- 25 February 2022 Haitian farmers displaced by Caracol project still await compensation By Sam Bojarski, Haitian Times

- 24 February 2022 As Haiti’s Caracol park grows, residents demand housing, roads, health care By Sam Bojarski, Haitian Times

- 23 February 2022 How an IDB land deal for Haiti’s farmers went wrong By Teresa Welsh, Devex

- 23 February 2022 3 years on, Haitians displaced by IDB project await land compensation By Teresa Welsh, Devex

- 5 August 2020 USAID needs an independent accountability office to improve development outcomes Margaux Day and Stephanie Amoako, Accountability Counsel in Devex

- 14 January 2020 Haiti farmers eager to receive compensation after ‘groundbreaking’ land deal By Jacob Kushner, Thomson Reuters Foundation

- 12 January 2020 10 Years Ago, We Pledged To Help Haiti Rebuild. Then What Happened?

- 23 September 2019 Gas shortages paralyze Haiti, triggering protests against failing economy and dysfunctional politics By Vincent Joos, The Conversation

- 29 March 2019 AAAS connects human rights groups with science experts By Andrea Korte, Science Magazine

- 7 March 2019 Former Robina Fellow Lani Inverarity ’15 Shares Win for Land Rights in Haiti By Yale Law School

- 4 February 2019 Fem bra saker som hände i januari By OmVärlden

- 29 January 2019 Displaced farmers’ coalition reclaims their road to sustainable livelihoods years after Haiti’s devastating earthquake By Janine Mendes-Franco, Global Voices

- 11 January 2019 IDB Settles Accountability Case in Haiti, Granting Land to Farmers By Teresa Welsh, Devex

- 11 January 2019 Haiti Update: Grassroots Victory in Caracol By Tom Ricker, Quixote Center

- 9 January 2019 Former Pathways Intern Continues Work to Protect Human and Environmental Rights By Sydney Speizman, Accountability Counsel, in The Kenan Institute for Ethics

- 20 December 2018 The Upside Weekly Report By The Guardian

- 27 April 2017 Inside the campaign to support communities harmed by development By Catherine Cheney, Devex

- 19 April 2017 USAID Forced Sweatshops on Haiti By Michael Kastner, Fee Stories

- 6 September 2016 The US promised to rebuild Haiti after the earthquake. Here’s what actually happened By Elizabeth Hagedorn, Circa

- 5 March 2015 How the US Plan to Build Houses for Displaced Haitians Became an Epic Boondoggle By Jake Johnston, Vice News

- 16 January 2015 The twisted tale of Caracol housing By Claire Luke, Devex

- 1 January 2015 Five years after quake, emerging northern Haiti faces challenges By Ángel González, Seattle Times

- 10 September 2014 A glittering industrial park in Haiti falls short By Jonathan M. Katz, Aljazeera America

- 16 January 2014 Outsourcing Haiti: How Disaster Relief Became a Disaster of its Own By Jake Johnston, Boston Review

- 8 May 2013 How Haiti’s Future Depends on American Markets By Tate Watkins, The Atlantic

- 14 February 2013 Will ‘Made In Haiti’ Factories Improve Life In Haiti? By Jason Beaubien, NPR

- 5 July 2012 Earthquake Relief Where Haiti Wasn’t Broken By Deborah Sontag, New York Times

Op-Eds

- 14 January 2019 Haiti Farmers Demanded Justice After Losing Their Land – Their Victory Shows What Empowering Workers Can Achieve By Lani Inverarity, Accountability Counsel, in Business & Human Rights Resource Centre

- 15 May 2017 Manufacturing a food crisis: Caracol Industrial Park, Haiti By Lani Inverarity, Accountability Counsel, & Joseph Wendy Alliance, ActionAid Haiti, for the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre

Blog Posts

- 15 March 2023 Haitian Farmers Request Final Push to Receive Full Compensation By Megumi Tsutsui and Sara Jaramillo, Accountability Counsel

- 28 January 2022 Haitian Farmers Begin Receiving Compensation, Demanding Swift Progress By Megumi Tsutsui, Accountability Counsel

- 9 January 2020 When HOPE is POWER: Haitian Farmers Defend Land Rights in Historic Dialogue Process By Lani Inverarity, Accountability Counsel

- 27 June 2017 Bank Agrees to Facilitated Dialogue with Displaced Haitian Farmers: Here’s Our Top Five Tips to Make This (or Any) Dialogue a Success

- 20 April 2017 The Dangers of Building Garment Factories Next to One of Haiti’s Most Important Marine National Parks

- 3 April 2017 Haitian Farmers Demand “konpansasyon jis” for Loss of Land: How We Are Working to Make This a Reality

- 7 March 2017 Supporting the Women of Caracol, Haiti this International Women’s Day 2017

- 24 January 2017 Haiti Land Grab Complaint Is Registered: Displaced Farmers Reflect on Their Fight for Justice

- 12 January 2017 On 7th Anniversary of Earthquake, Haitian Farmers File Land Grab Complaint Highlighting Harm Caused By Disaster “Recovery” Efforts

Press Releases

Photos

-

Loudrigeka's father cannot afford her school fees and fears for her future

Loudrigeka's father cannot afford her school fees and fears for her future -

Representatives of the Kolektif participate in a training session with Accountability Counsel attorneys

Representatives of the Kolektif participate in a training session with Accountability Counsel attorneys -

Members of the Komite, during a training session with Accountability Counsel attorneys

Members of the Komite, during a training session with Accountability Counsel attorneys -

Caracol Bay prone to possible contamination from the CIP

Caracol Bay prone to possible contamination from the CIP -

The Komite together with one of Accountability Counsel's attorneys

The Komite together with one of Accountability Counsel's attorneys -

Representatives of the Kolektif meet with MICI

Representatives of the Kolektif meet with MICI -

A local farmer grows manioc (cassava) in the fertile soils near the CIP site (ActionAid/Marilia Leti)

A local farmer grows manioc (cassava) in the fertile soils near the CIP site (ActionAid/Marilia Leti) -

Jean Lucien explains that, without the income from the land, he cannot pay his child's school fees

Jean Lucien explains that, without the income from the land, he cannot pay his child's school fees -

Marie Marthe Rocksaint, a farmer (ActionAid/Marilia Leti)

Marie Marthe Rocksaint, a farmer (ActionAid/Marilia Leti) -

Communities fear contamination of salt basins near Caracol Bay

Communities fear contamination of salt basins near Caracol Bay -

A banana plantation flourishes on the fertile soil near the CIP site

A banana plantation flourishes on the fertile soil near the CIP site -

Elie Josué holds a ledger of the seasonal workers he employed on his plot (ActionAid/Marilia Leti)

Elie Josué holds a ledger of the seasonal workers he employed on his plot (ActionAid/Marilia Leti) -

A smallholder farmer grows manioc (cassava) in the fertile soil near CIP site (ActionAid/Marilia Leti)

A smallholder farmer grows manioc (cassava) in the fertile soil near CIP site (ActionAid/Marilia Leti) -

Eva Baptiste, member of the Komite, whose family lost land at the CIP site

Eva Baptiste, member of the Komite, whose family lost land at the CIP site -

Etienne Robert's land was divided in two by the CIP (ActionAid/Marilia Leti)

Etienne Robert's land was divided in two by the CIP (ActionAid/Marilia Leti) -

Louis Tirène and Philomene Jean (ActionAid Haiti/Antoine Bouhey)

Louis Tirène and Philomene Jean (ActionAid Haiti/Antoine Bouhey)

- Agreement Status