Land

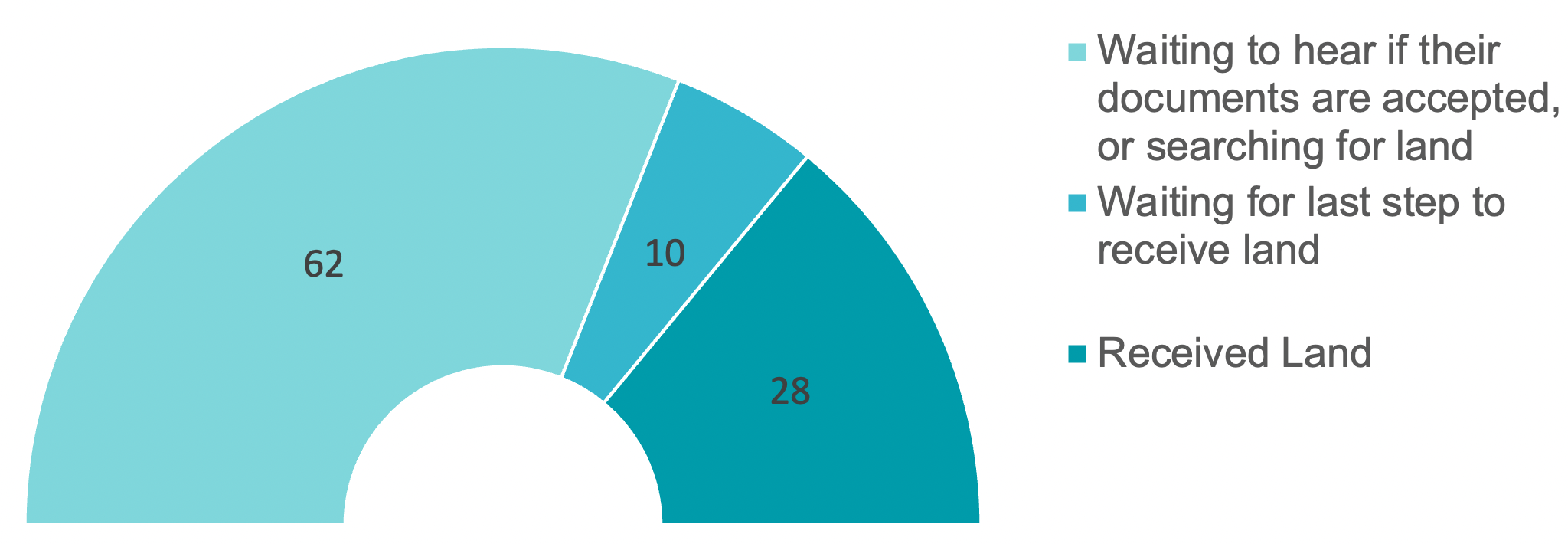

- In November 2021, the Kolektif Peyizan Viktim Tè Chabè celebrated an important milestone as the first 10 families received access to public land ten years after being displaced by the CIP. Since then, an additional 18 families have received land titles.

- 72 of the most vulnerable families are still waiting for their land.

- The IDB and the Haitian government must urgently: 1) support farmers to obtain documentation for this process, and 2) move those documents through the bureaucratic review as swiftly as possible.

For the farmers of Tè Chabè who were displaced to make way for the Caracol Industrial Park, their small plots of land were their life boats. They used their land to grow a diverse, bountiful, and healthy diet for their entire extended families, which often numbered 10 or more people. This included crops such as beans, okra, cassava, plantains, mango, pumpkin, peanuts, and rice among others. Their land not only provided food on the table, it was their main source of income and savings. Extra crops were grown and sold in the market to pay for their children to attend school, for vital medicines and medical care, and for any other emergencies the family might encounter. In short, their land was their entire livelihood, and when that was taken away, entire families’ lives significantly deteriorated and became much more precarious.

Given the importance of land to this community of farmers, this aspect of the agreement holds the most significance to them. After being forced from their land, many did not want to return to agricultural work, but about half of displaced families wanted to receive replacement land for what they had lost. In the end, compromises were made, and it was agreed that 100 of the most vulnerable displaced families would receive this benefit.

Four years after signing the Agreement, the Kolektif has celebrated 28 families receiving land as compensation, with 18 of those families receiving land in 2022 alone. This is a huge milestone in a country where land rights are often incredibly fraught with often informal, inconsistent, and confusing land titling and registration processes. Fifteen families received public land and three families received private land titles.

But 72 families identified as the most vulnerable among the displaced farmers are still waiting for land. Most of the 28 families who have received land received it in the form of public land owned by the Haitian State. These families are obtaining exclusive and significant rights to use the land for farming, but many families are concerned about the government’s lax enforcement of public land rights. One beneficiary who received public land had his land immediately seized by a neighbor through the use of force. The slow government response in approving and protecting public land has led many families to fear that they will never get the land they were promised.

The most critical challenges facing this process now are: (1) delays in the government’s bureaucratic process to review documents and communicate decisions to the beneficiaries; (2) the high standard of documentation being required, which is meant to follow all legal requirements, but is far more demanding than the local custom and practice; and (3) fuel shortages and a worsening economic and security situation which prevent travel to land plots for surveying and delay other necessary steps in the land process.

What is needed now is urgency. The IDB and the Haitian government have important roles to play in supporting people to obtain the higher standard of documentation demanded by this process and for shepherding those documents through the bureaucratic review as swiftly as possible. These families were displaced in 2011 — 12 years ago. Justice delayed is justice denied, and with every year and every day that goes by, these families experience not only the denial of their just compensation but also an ever-spiraling downturn towards hunger and greater insecurity.

Equipment

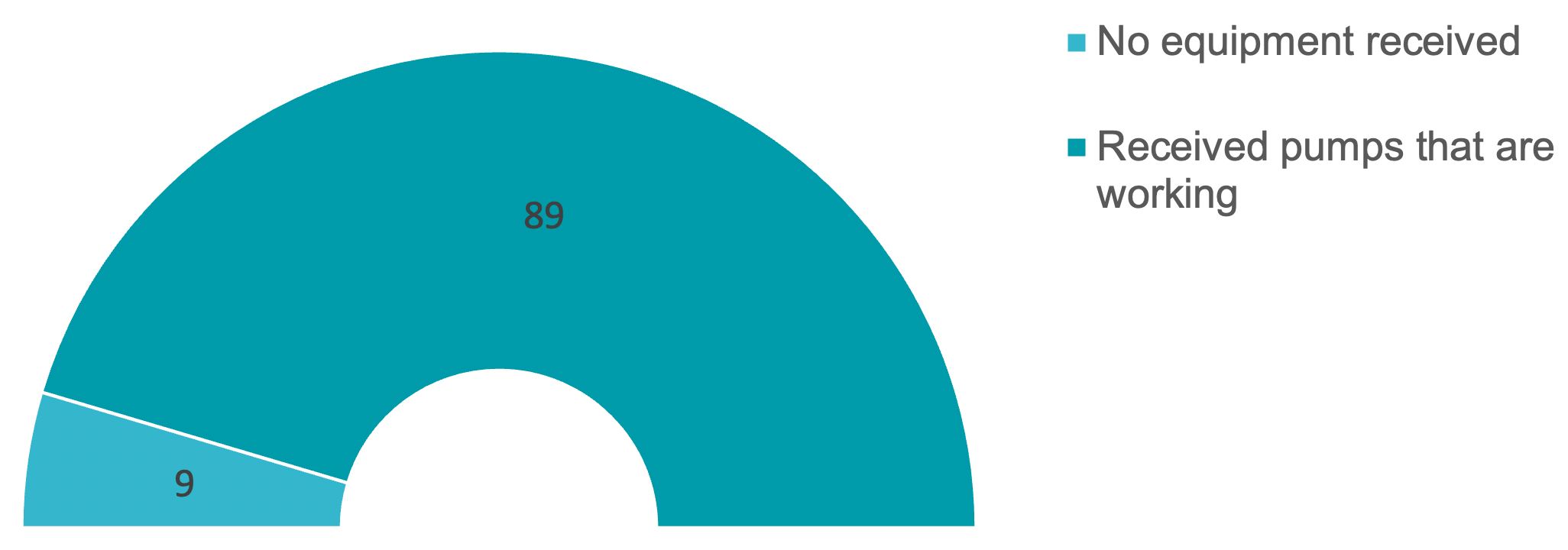

- Eighty-nine people received motorized well pumps. There are still nine people who were left off the equipment distribution list through no fault of their own, and who have been waiting to receive equipment for years.

- The IDB and the Haitian government must ensure that those nine families receive the benefits they were promised.

Some farmers who were displaced, managed to find other land they could farm to continue their livelihoods. Many in this group have stated that the alternative land they found has not been as productive as the land from which they were displaced. The land from which they were displaced was known as the most fertile in the area, irrigated by the Trou du Nord river which now bisects the Park. As part of the Agreement, people with access to land could elect to receive specialized farming equipment and technical support to improve the productivity of their land. Everyone who chose Equipment also chose to have a motorized pump installed on their land, which included the digging of a well from which the pump would extract water as well as pipes to distribute the water.

In August of 2020, the Haitian government distributed motor pumps to 64 out of 90 people who had signed up for this option. They arranged for wells to be dug for 63 of those people. Although some of those first beneficiaries had problems with their wells, those issues were successfully addressed this past year. In 2022, 26 more people received equipment.

This benefit has made a meaningful difference for those who have been fortunate to receive their equipment. Unfortunately, fuel shortages have impacted individuals’ ability to operate the pumps and fully reap the benefit of this program. This has highlighted how the multiple crises in the country have continued to prey on the vulnerability of this group.

The IDB and the Haitian government must urgently work towards finishing what they started. The nine people who are still waiting to receive equipment have been in the dark for years, without clear explanations for why they have not received wells and pumps. Some of them are sick and struggle to afford medical bills, and many struggle to eat more than one meal a day. In an area prone to drought and weather exacerbated by climate change, these wells and motorized pumps are proving to be a vital tool to help farmers sustain their livelihoods. The last nine beneficiaries have waited long enough and should receive their equipment as soon as possible before having to forego greater productivity on another planting season.

Small Business

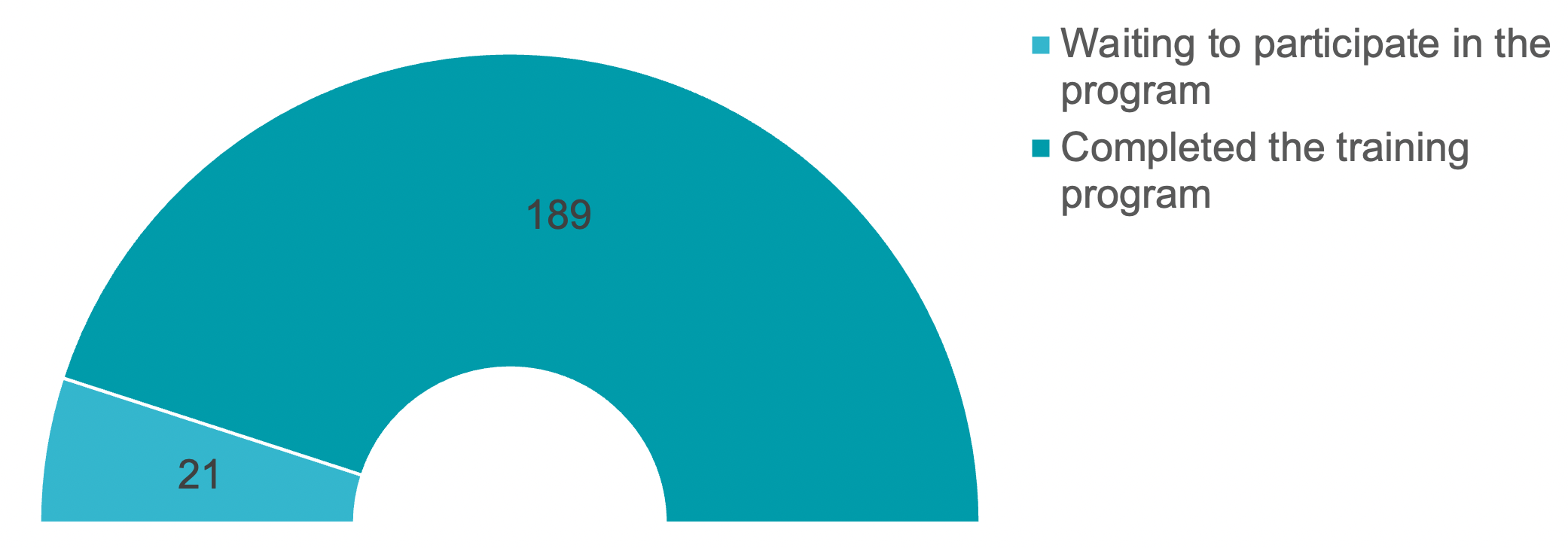

- 189 people received support in starting a small business, including training, health insurance, start-up assets, and access to microcredit. An additional 21 participants were prevented from joining the first group and are still waiting for this benefit.

- The Kolektif, the IDB, the Haitian government, and the local implementer were able to reach an agreement to adapt the program methodology after currency exchange volatility and inflation eroded the original value of the program. In light of continued double-digit inflation in Haiti, the IDB should once again adapt the program for this last group to account for economic changes.

Those without access to land were offered training and support to start a small business as an alternative livelihood to farming. All participants in this category receive training, health insurance, start-up assets, and access to microcredit in the form of a zero-interest lending circles.

This program met with a lot of community resistance at the outset of implementation, particularly as currency exchange volatility and year over year double digit inflation eroded the value of the program and many believed that this program was not as valuable as the equipment program.

Last year, after extensive community consultation, the Kolektif, the IDB, the Haitian government, and the local implementer of the program Sonje Ayiti, were able to reach an agreement to adapt Sonje Ayiti’s methodology to address important changes in economic conditions. This proved to be an important lesson that implementation of an agreement to restore livelihoods can encounter significant delays impacting the value of the agreement. In this situation, all the Parties demonstrated flexibility and a willingness to listen in order to maintain the community’s trust in the process and ensure people received the same value they expected when the agreement was signed.

The program provided 189 participants with weekly mentoring and four training sessions on entrepreneurship, veterinary care, savings and credit, and building confidence. Initial feedback for the program was positive, and many in the program expressed gratitude for being provided access to health insurance for the first time, and for being able to engage in economic activities generating income for their families. But the hardships of the past year have made it difficult for many to maintain their small business. Many participants we interviewed in 2022 spoke about needing to use any profits from their small business on basic necessities like food or school fees for their children.

An economic adjustment is needed. Twenty-one more families are still waiting for this livelihood support. To ensure that they meaningfully benefit from it, the IDB and the Haitian government should make appropriate adjustments to the program to account for double-digit inflation, which has eroded the value of what was promised.

Vocational Scholarships

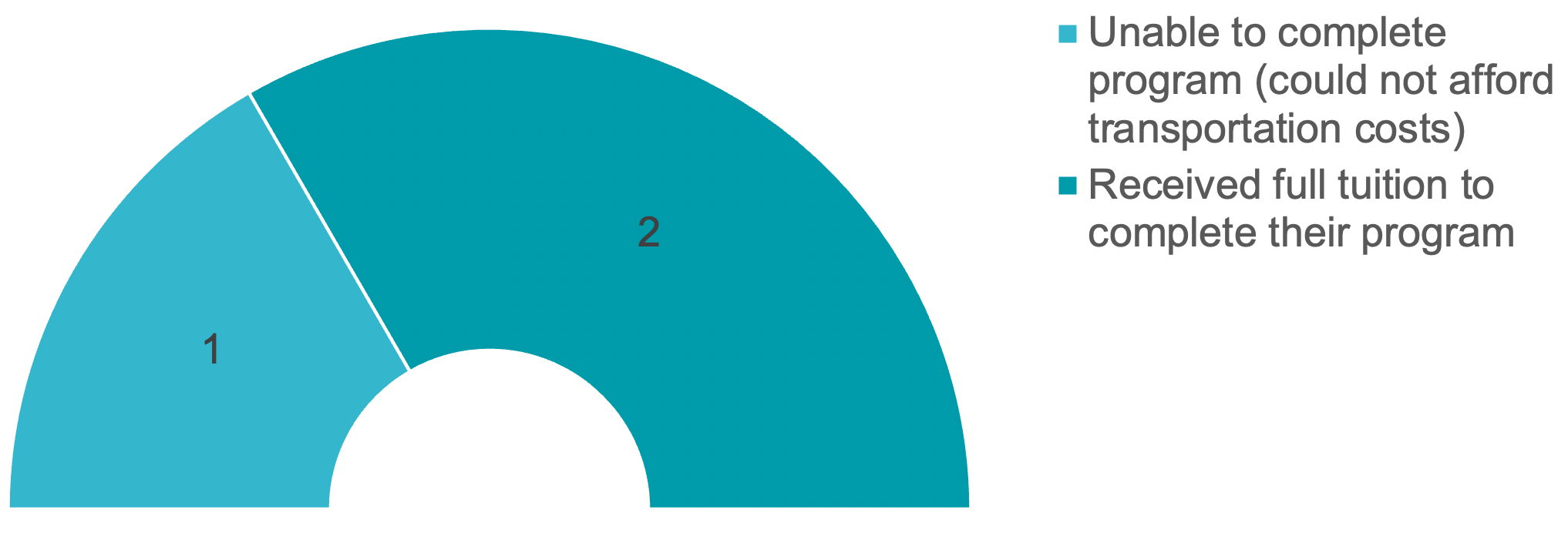

- Three beneficiaries received a scholarship for technical training and are currently enrolled in their program of study.

- Though other programs have received adjustments to account for delays and the deteriorating value of the agreement, this program has received limited changes and one person needs additional support to fully realize the benefit of their program.

The final option for restoring livelihoods involved receipt of a scholarship for one year at a qualified technical training institution to study a trade. This was a difficult option for most people to access because attending school for a year meant possibly incurring more costs (for example in transportation) while delaying the ability to generate income for an entire year.

Only three people chose this option. One enrolled in courses but could not attend classes because the cost of fuel had increased significantly since the agreement was signed making travel to school impossible. She has pleaded for support to help her access this benefit to no avail.

One person needed additional tuition support to finish the second year of the program to fully benefit from the training. The IDB and Haitian government supported this person with that request. One person graduated from their program in December 2021 and expressed optimism about his studies translating into a job providing more economic security.

Employment

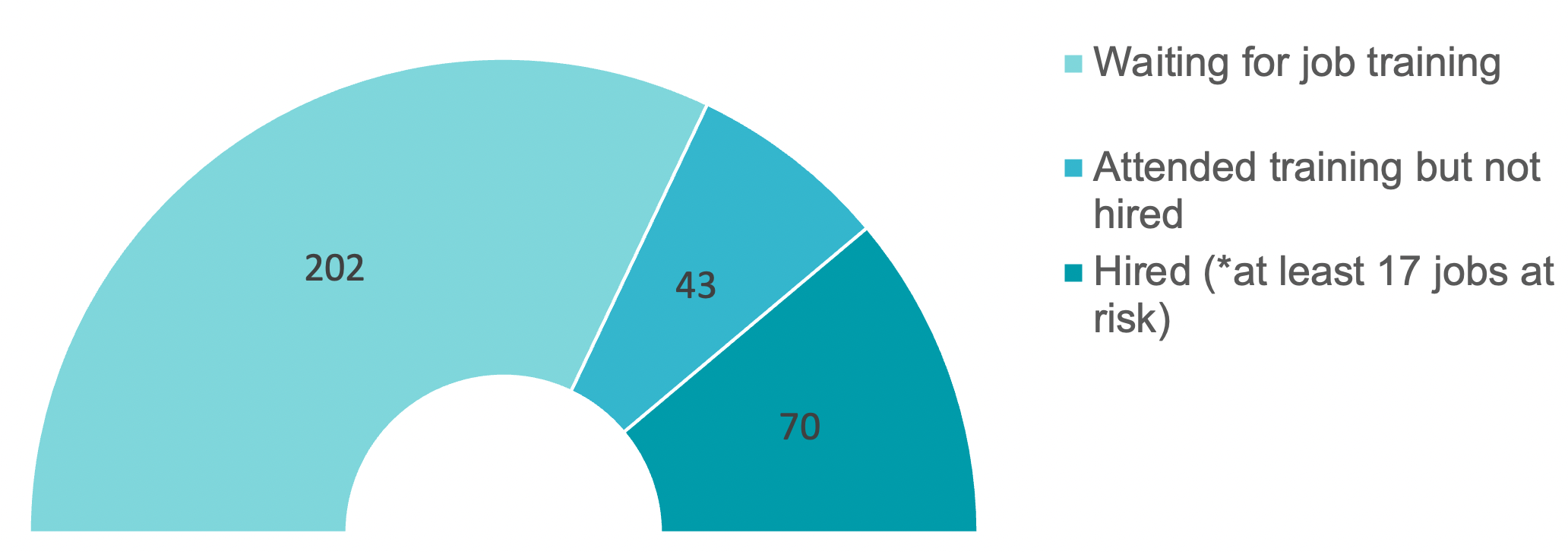

- The IDB and UTE committed to coordinating with companies at the CIP to identify employment opportunities for each affected household. Initially, only 45 out of 315 individuals were hired and provided with sewing jobs (14% hiring rate).

- After the IDB and the UTE agreed to pilot access to training at the Park’s training center, approximately 68 individuals were provided with training and 25 of them were hired for sewing jobs at the Park (37% hiring rate).

- This training program stopped during the pandemic and has yet to be restarted. Only 70 people out of 315 who expressed interest have been hired to sewing jobs. Not a single person has been hired to a more specialized job, when 30 of these positions were promised. This training program should continue so that other affected families can access this vital income opportunity.

The Caracol Industrial Park that displaced farmers was meant to create jobs that would allow additional members of families to contribute to household income outside of agriculture. The agreement promised that in addition to the main livelihood supports (land, equipment, small business training, vocational scholarships), one member from each affected family would be eligible for employment at the Park after receiving preparatory technical training. The majority of the jobs would be in sewing, with 30 being in more technical roles.

This benefit was meant to be implemented immediately so that households would have quick access to additional income while the main livelihoods support got underway. However, companies at the Park opted not to contribute to providing preparatory technical training before engaging in hiring, and out of 315 applications only hired 45 individuals (14% hiring rate).

In response to advocacy from the Kolektif, the UTE and IDB agreed to guarantee access to training at the Park’s newly established training center to help ensure access to employment at the Park. Approximately 68 people were provided with training through the training center, leading to 25 people being hired (37% hiring rate). The training program was received positively by the community. During the COVID pandemic, the training program was stopped and has yet to resume.

This training program must be continued to fulfill the promise of livelihood restoration as agreed by all the Parties. The Final Agreement saw employment at the CIP as an integral remedy for those who were displaced by the Park. Ending the program now would be a grave mistake, going against clear progress and depriving Kolektif members from full access to the income-generating activities to which they are entitled. The Kolektif have requested common sense interventions to improve the program, such as having a point person at the Park’s hiring center to consult for jobs and providing certificates for those who have completed the training course.

If the IDB and UTE cannot fulfill their obligations in the Agreement, they must provide an alternative — the harm they caused to the Kolektif cannot be remedied without this additional income-generating support.

School Kits

- Each family was provided with two school kits, which included notebooks, backpacks, pencils, pens, and geometry sets; however, 90% of all distributed backpacks tore and broke within days of receiving them.

- The IDB and UTE consulted the Komite on a new backpack to distribute, and have since made these backpacks available to all families.

One of the most difficult trade-offs that families had to make when they lost their land and their livelihoods is whether they had enough to meet their basic needs and pay for the fees and costs needed for their children to attend school. In Haiti, schools charge a fee for attendance and often require that students pay for other costs such as books, supplies, and uniforms.

The agreement intended to provide some measure of support to families to lessen the burden of school costs by giving each family two school kits, which included notebooks, backpacks, pencils, pens, and geometry sets. This was the first benefit people received, and many families expressed dissatisfaction when their backpacks tore within days of receiving them.

This proved to be the first test the Parties would face in terms of how they would deal with challenges presented during implementation. The Komite conducted a survey within the community to assess the size of the issue and presented the results of their survey and physical evidence that indicated the problem affected about 90% of all distributed backpacks and therefore all backpacks should be replaced. The IDB and UTE accepted these results, consulted the Komite on a new backpack to distribute, and then made these new backpacks available to all the families.

This moment provided an important lesson for the Komite, as they realized that it was important to check the quality of items before they were distributed to try to catch these issues earlier in the process when they were easier to address. They have since insisted on seeing items such as water pumps, and agricultural tools, before they are distributed to assess their quality.

Environmental & Social Safeguards

- Affected families continue to worry about the Park’s wastewater contaminating vital water resources and trash piles contributing to harmful pollution.

- In the 2018 Agreement, the IDB committed to improving in the areas of solid waste, wastewater treatment, stakeholder engagement, emergency response, and implementation of the EHS system, but these issues remain largely untouched.

- The Haitian government and the IDB must meet their minimum social and environmental obligations before the Bank distributes an additional $65 million investment to the Park.

“The Bank continues to work to improve the social and environmental management of the CIP and considers the Kolektif’s support in this task to be crucial.”

-Agreement

Farmers who were displaced by the Park also complained about the lack of information and consultation related to the environmental and social impacts of the Park. They continue to worry about the Park’s impact on vital water resources such as pollution of the Trou-du-Nord River and contamination of local groundwater. For years the local community has complained about the immense trash piles where solid waste from the Park was disposed, and which caught on fire in 2020 contributing to harmful air pollution for all those living next to the trash piles. Fires at these trash piles continue to be a problem affecting the communities living nearby.

The IDB in the 2018 Agreement committed to continuing to improve in the areas of solid waste, wastewater treatment, stakeholder engagement (inside and outside of the CIP), emergency response and implementation of the EHS system. These issues have yet to be fully addressed, even though the IDB’s policies require mitigation and remediation.

As the Bank recently committed an additional $65 million investment in the Park, all eyes will be on the UTE and IDB to see if they will hold to their promise to resolve these issues before more money is disbursed to a project that is not able to meet its minimum obligations to prevent and mitigate social and environmental harm.

The Kolektif urges the Bank and the Haitian government to follow through on their Environmental & Social commitments in the Agreement, which include:

- Improving in the area of: solid waste, wastewater treatment, stakeholder engagement (inside and outside of the CIP), emergency response and implementation of the EHS system;

- Strengthening the grievance mechanism inside and outside the CIP. This will include seeking a place to receive requests for information and/or written grievances in a confidential manner;

- Engaging a laboratory to perform independent water analyses to be shared with the Kolektif and published online; and,

- Providing detailed updates to the Kolektif on environmental and social issues during meetings of the Monitoring Committee, which will be included in the annual public monitoring report produced by MICI.