Kenya: Lamu Coal-Fired Power Plant

-

Overview

Communities are taking action to stop a proposed 1,050 MW coal-fired power plant on the Lamu coast in Kenya to protect their environment, culture, and livelihoods from irreversible harm. They are succeeding.

The proposed coal plant posts existential threats to Lamu’s two most important

economic activities: fishing and tourism.The risks of constructing a coal plant in Lamu are grave. Lamu County is home to Lamu Old Town, a UNESCO-recognized World Heritage site. UNESCO itself has called for the end of the project, due to negative impacts on the World Heritage site. The area also hosts 70% of Kenya’s critically important coastal mangrove forests. The coal plant would result in serious air, water, and land pollution, a decline in marine resources, and destruction of internationally-recognized natural habitats.

The US$2 billion project is being developed by Amu Power, a joint enterprise of Kenyan firms Gulf Energy and Centum Investment. Despite recent news that its biggest financier, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, has pulled out of the project due to environmental and social risks, Amu Power claims that the project will continue. This latest news compounds doubts about the necessity and economic viability of the project.

No efforts been made to remediate the families already harmed. At least 109 families have already been left without income or food security, having been displaced from their farmland without compensation.

If the project continues, thousands more families face a loss of land or livelihoods. Indigenous communities will lose access to critical resources that they have sustainably managed for generations.

Despite these significant risks and impacts, communities have not been consulted, and project proponents have ignored their concerns. On June 26, 2019, the National Environment Tribunal (NET) of Kenya agreed, invalidating the coal plant’s environmental license for lack of effective public participation, among other reasons: “It is presumptuous for a proponent, like the [Amu Power] did in this case, to proceed with the EIA study, identify the impacts and then unilaterally provide for mitigation measures in complete disregard of the people of Lamu and their views. We therefore find that public participation…was non- existent and in violation of the law.”

The NET decision, UNESCO’s criticism of the project, and the exit of various financiers have all validated years of struggle by Save Lamu and a broad coalition of other groups to document the project’s profound risks and consultation failures. Accountability Counsel’s support for this movement has focused on raising community demands that international investors take immediate steps to end their participation in the project. To that end, in April 2019, Accountability Counsel and Natural Justice supported two community organizations, Save Lamu and the Kwasasi Mvunjeni Farmers Self-Help Group, to file a complaint (also available in Kiswahili) to the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO) of the International Finance Corporation (IFC) of the World Bank. The complaint described IFC contributions to the coal plant project through three banks, which provided loans to Centum Investment after receiving IFC funds. The complainants requested that the CAO conduct an investigation into the potentially disastrous project.

In July 2019, however, the CAO found the complaint ineligible, determining that the links to the IFC did not constitute active, material exposure to the project. The decision was especially disappointing in that it confirmed a pattern of IFC support for the project, such that the complaint may have been eligible had it been filed at an earlier point in time. The lack of transparency regarding the IFC’s financial intermediary links to problem projects, like the Lamu coal plant, make it difficult, if not impossible, for complainants to know in advance whether such complaints will be eligible.

The CAO complaint is a continuation of many years of work with Save Lamu to raise their communities’ concerns about the coal plant, as well as other infrastructure mega-projects planned for Lamu County. Lamu is a major hub along the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia (LAPSSET) Corridor, described by the Kenyan government as East Africa’s largest and most ambitious infrastructure project. These developments, separately and together, threaten to permanently and dramatically disrupt the unique character, culture, and environment of the entire Lamu archipelago.

“We are grieved that whatever ecological value the site has now will be permanently lost. We fear the ash will be blown by our monsoon winds and may settle on nearby houses, vegetation, and ocean. There can also be runoff of these pollutants by rain and this will contaminate both our lands and water.” — Lamu resident

-

The Story

A majority of communities in Lamu still depend on nature-based livelihoods such as

fishing, mangrove cutting, hunting and gathering, pastoral livestock keeping, farming,

eco-tourism and many othersIf constructed, the 1,050 megawatt coal-fired power plant planned for the Lamu coastline will be the first coal plant in Kenya and the biggest in East Africa.

Local communities face devastating impacts on their health, food security, environment, cultural heritage, and livelihoods from the construction and operation of the coal plant.

Lamu County is internationally-recognized for the richness of its environment, including its marshlands, grasslands, savannahs, baobab and mangrove forests, coral reefs, beaches, and sand dunes.

The proposed 975-acre coal plant site is on the Lamu mainland, adjacent to vitally important coastal mangrove forests that protect against erosion and flooding and serve as a breeding ground and nursery habitat for various fisheries. The construction of a coal plant will destroy mangroves and require dredging the seafloor. Operation of the plant will continue the devastation. The coal plant’s cooling system will pull in huge amounts of seawater from Manda Bay, trapping marine life in the intake process. Water will be returned by this system into Manda Bay, desalinated and at a higher temperature, inflicting further damage on the delicate marine environment.

The land for the coal plant site is being compulsorily acquired from local farmers, who, years after displacement was announced, continue to face uncertainties around the extent and type of compensation and resettlement support they will receive. At least 109 farmers and their families have already been displaced by the construction of the site access road, without any consultation or compensation. Thousands of other land users, fisherpeople, and tourism operators, including indigenous and other vulnerable communities, are expected to lose their livelihoods.

“At my homestead, cashew nut trees were cut down for the road, while I was away. My farm, the road cuts down the middle of it. I wasn’t around. It was off-season. … They came with machines. They came here and destroyed our trees. I wasn’t consulted at all. To date, I have not been informed of anything at all. No sort of communications. Here we are. This has left me wondering, are we baboons, animals, or are we humans? It would even be better to be an animal than to be treated like this.” – A Kwasasi farmer displaced by the site access road

The unique cultural heritage of Lamu Old Town, which is recognized by UNESCO as a

World Heritage Site, faces existential threats from the proposed Lamu coal plantThe proposed site for the coal plant is approximately 20 km north of Lamu Old Town, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, recognized as the oldest and best-preserved Swahili settlement in East Africa. It is a small, conservative, and preserved society, maintaining its traditional architecture and its distinct social, cultural, and religious functions up to the present day. This distinct culture faces major threats from population and development pressures, loss of traditional livelihoods and environmental degradation. UNESCO itself has called for the end of the project, due to negative impacts on the World Heritage site.

Lamu is also home to many indigenous communities who have carved out distinctive livelihoods over the centuries utilizing the rich and diverse marine, coastal, forest, and grassland environments of the archipelago. These communities face displacement from the project site, adverse impacts on their livelihoods and cultural heritage, and loss of access to traditional land and resources in and around the project site. Impacts from the coal plant will exacerbate losses already suffered as a result of other LAPSSET developments, including the Lamu port.

Like all other coal plants, the Lamu coal plant will emit many chemicals and particulates that are linked to severe health and environmental impacts. In addition to the human and environmental toll, the delicate coal stone buildings found in Lamu Old Town, and elsewhere in Lamu, will be particularly vulnerable to acid rain and other air pollution caused by the coal plant. Toxic ash waste will be stored in a dry ash yard, where communities fear it will be at risk of catastrophic destabilization during monsoon season.

Serious doubts also remain about the necessity and economic viability of this project, which will lock the country into a 25-year power purchase agreement, forcing Kenyan electricity consumers to pay more than $9 billion even if the coal plant does not generate any power.

“There is … a potential of not only marginalizing the community but total disruption of a tradition and all sustaining traditional lifestyle developed and nurtured over millennia with the attendant loss of their heritage.” – Heritage Impact Assessment, cited by UNESCO

Despite the significant risks, project developers have not consulted threatened communities and have ignored their concerns for years. Information provided in the few community meetings that were held was superficial, inaccessible, inaccurate and unbalanced. Subsequent project documents failed to genuinely respond to any of the comments and concerns that were expressed during those earlier community meetings. On June 26, 2019, the National Environment Tribunal (NET) of Kenya agreed, invalidating the coal plant’s environmental license for lack of effective public participation, among other reasons: “It is presumptuous for a proponent, like the [Amu Power] did in this case, to proceed with the EIA study, identify the impacts and then unilaterally provide for mitigation measures in complete disregard of the people of Lamu and their views. We therefore find that public participation…was non- existent and in violation of the law.”

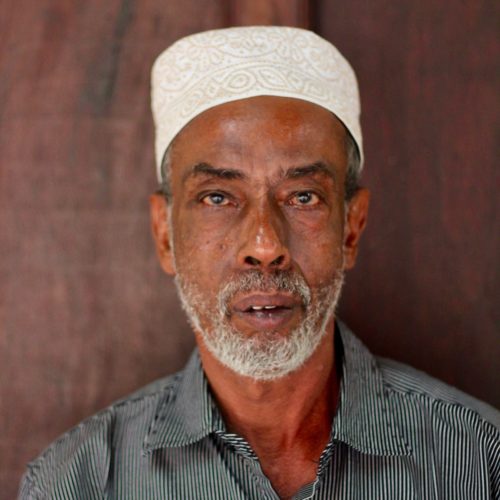

Chairman of Save Lamu (Credit: Desiree Knoppes)

Some affected groups, including the farmers displaced by the site access road, were not consulted at all. And shockingly, a pattern of intimidation by government officials has impeded attempts by local groups to hold information sessions to engage and discuss project impacts as a community.

Communities are now taking action to raise their concerns to the investors in the coal plant, including the World Bank Group’s International Finance Corporation (IFC). On 26 April 2019, two community groups, Save Lamu and the Kwasasi Mvunjeni Farmers Self-Help Group, filed a complaint (also available in Kiswahili) to the IFC’s accountability office, the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO), to voice their concerns about serious violations of the IFC’s Performance Standards in the development of the proposed coal plant. Despite pledging to avoid new investments in coal projects, the complaint described IFC contributions to the coal plant project through through three financial sector clients: the Co-operative Bank of Kenya, FirstRand Bank, and Kenya Commercial Bank. Each of these banks provided loans to Centum Investment, one of the coal plant’s developers, after receiving IFC funds. The complaint was filed with support from Accountability Counsel and Natural Justice.

The complainants requested that the CAO conduct an investigation into the potentially disastrous project. In July 2019, however, the CAO found the complaint ineligible, determining that the links to the IFC did not constitute active, material exposure to the project. The decision was especially disappointing in that it confirmed a pattern of IFC support for the project, such that the complaint may have been eligible had it been filed at an earlier point in time. The lack of transparency regarding the IFC’s financial intermediary links to problem projects, like the Lamu coal plant, make it difficult, if not impossible, for complainants to know in advance whether such complaints will be eligible.

“It is problematic for the IFC to be found investing in financial intermediaries that are funding the Lamu coal plant project, especially given that the World Bank has pledged to divest from coal. It is very clear that the anticipated impacts from the project threaten the human rights of the communities living in the region and their environment.” – Rose Birgen, Senior Program Officer at Natural Justice

While activists awaited the results of the complaint filed with the National Environmental Tribunal (NET) of Kenya, they continued to put pressure on the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), one of the largest investors in the Lamu project. Activists went to the bank’s investors to persuade them to pull out of the project. They posted messages on the bank’s social media channels and wrote letters to raise awareness amongst the public. In June 2019, activists protested at the Chinese embassy in Nairobi at the ICBC office. In response, the ICBC stated that only the Kenyan government can stop the project. However, in a victory for the civil activists, the ICBC ultimately completely withdrew from the project in November 2019. Following the ICBC’s withdrawal from the project, the Kenyan government has made statements suggesting it may not move forward with the project.

History

Businessmen, fishermen and farmers in Old Town, Lamu Island

In September 2014, the government awarded the contract for the coal plant to Amu Power, a special-purpose vehicle established by Gulf Energy, a privately held Kenyan energy company, and Centum Investment, a publicly traded Kenyan investment firm.

According to an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment dated July 2016, the coal plant will include three supercritical coal-fired thermal generating units. (Despite US multinational General Electric’s May 2018 announcement that it would be providing ultra-supercritical technology to the Lamu coal plant, no updated technical assessments have been published.) The power plant will burn about 2.8 megatons (Mt) of coal per year. The facility will operate 24 hours per day, seven days per week. The coal plant will also require the following infrastructure:

- Limestone mining at Witu. A 2,000-acre mining concession has already been approved by local authorities. Limestone is needed for a pollution control system called wet flue gas desulfurization. The limestone will be transported by land and sea to the power plant;

- A coal receiving system including a coal berth at Lamu port, coal handling equipment and a conveyor system approximately 15 km long to transport coal from the port to stockyards;

- Two coal stockyards, with capacity for up to 420,000 metric tons of coal;

- A 400 kV substation;

- A permanent workers’ colony accommodating 250-300 persons;

- A new rail system to transport coal if Kenyan coal becomes available; and

- Associated roads, buildings and other structures.

Construction of the coal plant itself is yet to begin, although development of the site access road – and associated displacement of Kwasasi farmers – is underway. The project was stalled for many years after Save Lamu and other Lamu residents appealed the granting of the environmental licence to the project at Kenya’s National Environment Tribunal.

The first three berths of the Lamu deep sea port under construction

The proposed Lamu coal plant and its impacts can only be fully understood in the context of the LAPSSET Corridor mega-project, described by the Kenyan government as East Africa’s largest and most ambitious infrastructure project. Major components of LAPSSET to be located in Lamu include:

- A 32-berth deep sea port;

- An industrial facility near the port, including oil-refining and petrochemical factories;

- Railway, road, and highway networks connecting South Sudan and Ethiopia to the port in Lamu;

- Lamu-Lokichar crude and product oil pipelines;

- A resort city and a new airport ;

- A new Lamu metropolis on the mainland, expected to host one million residents by 2030;

- All the necessary support infrastructure for metropolis development.

These projects are closely intertwined. The LAPSSET Corridor Development Authority is the entity acquiring the land on which the Lamu coal plant is proposed to be built.

The early stages of the port construction have already required significant mangrove clearance, dredging and reclamation of land. In 2018, in litigation filed by Lamu residents including members of Save Lamu, the High Court of Kenya awarded 1.7 billion KSh as compensation to 4,700 fisherpeople affected by the Lamu port development, in recognition of failures to respect their traditional rights. The piecemeal assessment of LAPSSET-related projects has failed to fully recognize the social and environmental impacts of LAPSSET as a whole. Directly as a result of the likely negative impacts on Lamu Old Town, a World Heritage Site, UNESCO has repeatedly requested that construction of various LAPSSET-related projects be halted “in order to allow time for a full assessment of its wider direct and indirect impacts on the property and for appropriate mitigation measures to be defined and implemented.” That cumulative impact assessment is yet to be undertaken.

“We, the community of Lamu, rely on our natural resources to survive – for nourishment, shelter, healthcare, to worship in our sacred spaces, and to continue our cultural traditions. Our environment is our wealth – when our environment is healthy, we are healthy. When our environment suffers, we suffer.”

After the success of pressuring the ICBC and its investors to withdraw from the project, together with Save Lamu, the Kwasasi Mvunjeni Farmers Self-Help Group, Natural Justice and other partners, our focus remains to continue to pressure investors and other key stakeholders to divest from this harmful project.

Initial Steps

Kwasasi farmers displaced by the site access road

At an earlier stage, the African Development Bank (AfDB) was considering providing a partial risk guarantee covering Kenya Power and Lighting Company’s obligations under a 25-year Power Purchase Agreement related to the coal plant. However, following advocacy by Save Lamu and others highlighting deficiencies in the project’s environmental and social impact assessments, that support has not yet been approved and further discussions appear to have been postponed.

In contrast to this community victory, members of Save Lamu and the Kwasasi Mvunjeni Farmers Self-Help Group have tried for years to raise their concerns with other project stakeholders and relevant government authorities, with no success. In stakeholder consultation meetings, questions were not answered or were answered dismissively, with misleading information. In addition, complainants have provided comments in writing, directly to Amu Power, its shareholders (Gulf Energy and Centum), its investors (including the IFC) and relevant government authorities, and indirectly through official consultation processes. Despite these good faith attempts to engage, they have never received a substantive, detailed response to their concerns. Instead, a pattern of intimidation by government officials has impeded attempts by local groups to hold information sessions to engage and discuss project impacts as a community.

The Complaint

Because of the lack of responsiveness of project developers, communities are also raising their concerns directly with the project investors. While many details of the project financing remain hidden from the public, the complaint described probable IFC contributions to the Lamu coal plant through three clients: the Kenya Commercial Bank, the Co-Operative Bank of Kenya and the FirstRand Bank. After receiving funds from the IFC, those banks provided financial support to Centum Investment, a co-developer of the coal plant.

On 26 April 2019, Save Lamu and the Kwasasi Mvunjeni Farmers Self-Help Group, with support from Accountability Counsel and Natural Justice, filed the complaint to voice concerns about serious violations of the IFC’s Performance Standards in the development of the proposed coal plant.

The 88-page complaint details a vast number of violations of those standards, including that:

- The environmental and social impact assessments fail to analyze critical aspects of the project.

- Affected people were not adequately identified or consulted.

- Thousands of farmers, pastoralists and other land users, fisherpeople, and tourism operators, including indigenous and other vulnerable communities, are expected to be displaced, with no comprehensive resettlement or compensation plans in place.

- Pollution and biodiversity impacts have not been properly assessed or mitigated.

- The risks posed by this project to Lamu’s unique cultural heritage have been grossly underestimated.

- No real consideration has been given to other, less-polluting, energy sources or to alternative project sites.

- There has been no genuine assessment of cumulative impacts, despite the fact that Lamu is a central node along the planned LAPSSET Corridor.

- There is no broad community support for this project.

A more detailed summary of the complaint is available in English and Kiswahili.

“We have plenty of renewable sources of energy in Lamu; we see the sun for 12 months. Kenya can make use of these sources to produce energy without harming our environment, the resources we depend for our livelihoods, not even our health,” – Khadija Shekuwe, Coordinator of Save Lamu

The complaint requested that the CAO independently investigates the coal plant’s compliance with the IFC’s standards – a process known as compliance review. In July 2019, however, the CAO found the complaint ineligible, determining that the links to the IFC did not constitute active, material exposure to the project. The decision was especially disappointing in that it confirmed a pattern of IFC support for the project, such that the complaint may have been eligible had it been filed at an earlier point in time. The lack of transparency regarding the IFC’s financial intermediary links to problem projects, like the Lamu coal plant, make it difficult, if not impossible, for complainants to know in advance whether such complaints will be eligible.

Together with Save Lamu, the Kwasasi Mvunjeni Farmers Self-Help Group, Natural Justice and other partners, we will continue to pressure investors and other key stakeholders to divest from this harmful project.

Case Partners

Save Lamu: a Kenya-based umbrella organization that represents over 40 organizations from Lamu, Kenya. Save Lamu’s mission is “to engage communities and stakeholders so as to ensure participatory decision-making, achieve sustainable and responsible development and preserve the environmental, social and cultural integrity of the Lamu community.”

Kwasasi Mvunjeni Farmers Self-Help Group: a group of farmers whose farms were destroyed because of the construction of the access road linking Lamu Port to Kwasasi, to provide site access to the proposed Lamu coal plant. To date, the farmers have not been consulted or compensated regarding these impacts. The Group formed in 2017 in order to seek accountability and remedy for this harm.

Inclusive Development International

-

The Case

-

Nov 2020

The Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), one of the largest investors in the Lamu project, completely withdrew from the project following months of direct advocacy by activists.

-

Aug 2019

Save Lamu and the Kwasasi Mvunjeni Farmers Self-Help Group wrote to the World Bank raising concerns about World Bank support for development of the Lamu coal plant through World Bank projects aimed at generating “bankable” public private partnerships in Kenya.

-

Jul 2019

The CAO found the complaint ineligible, determining that the links to the IFC did not constitute active, material exposure to the project. The decision was especially disappointing in that it confirmed a pattern of IFC support for the project, such that the complaint may have been eligible had it been filed at an earlier point in time. The lack of transparency regarding the IFC’s financial intermediary links to problem projects, like the Lamu coal plant, make it difficult, if not impossible, for complainants to know in advance whether such complaints will be eligible.

-

Jun 2019

Save Lamu and other members of deCOALonize met with the Chinese ambassador to Kenya to discuss concerns with the Lamu coal plant. It was Save Lamu’s first meeting with the Chinese government since it began reaching out through the Chinese embassy in Nairobi in 2016.

-

Jun 2019

The National Environment Tribunal (NET) of Kenya invalidated the coal plant’s environmental license for lack of effective public participation, among other reasons: “It is presumptuous for a proponent, like the [Amu Power] did in this case, to proceed with the EIA study, identify the impacts and then unilaterally provide for mitigation measures in complete disregard of the people of Lamu and their views. We therefore find that public participation…was non- existent and in violation of the law.”

-

Jun 2019

The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) published a critical of the coal plant entitled The Proposed Lamu Coal Plant: The Wrong Choice for Kenya.

-

May 2019

Save Lamu wrote to the Chinese Embassy reiterating concerns over the proposed Lamu coal plant, and requested that the Chinese Embassy to encourage ICBC to consider suspending financing to the coal plant given the serious design and community consultation flaws of the project. No response from the Chinese Embassy was received.

-

May 2019

Save Lamu wrote to the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) reiterating concerns over the serious environmental, social, and cultural risks of the proposed Lamu coal plant, and the lack of meaningful community consultation in the design of the project. Save Lamu requested that ICBC suspend financing of the coal plant. No response from ICBC was received.

-

May 2019

Save Lamu wrote to the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO) of the International Finance Corporation (IFC), providing supplementary information to their complaint.

-

Apr 2019

Save Lamu and the Kwasasi Mvunjeni Farmers Self-Help Group, with support from Accountability Counsel and Natural Justice, filed a complaint (also available in Kiswahili) to the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO) of the International Finance Corporation (IFC). Given the profound risks of the Lamu coal-fired power plant, they are asking international investors to take immediate steps to end their participation in the project. The complaint was filed with a cover letter by Accountability Counsel as advisors, explaining why the IFC’s connections to the coal plant project are material.

A summary of the complaint is available in English and Kiswahili.

-

Feb 2019

General Electric responded to Save Lamu’s letter, stating that General Electric has no ownership interest in the Lamu coal plant project.

-

Feb 2019

Save Lamu wrote to the Chinese Embassy. The letter outlined environmental, social, legal, and public questions regarding the feasibility and impacts of the proposed Lamu coal plant, and raised concerns over ICBC’s continued failure to respond to Save Lamu’s requests for information. No response from the Chinese Embassy was received.

-

Feb 2019

National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) responded to Kwasasi Farmers Self Help Group’s letter to the Chairman of the National Land Commission. In their response, NEMA stated that they are planning to make a site visit to Kwasasi area to investigate the matter, and establish whether an EIA was done for the road.

-

Jan 2019

-

Nov 2018

Kwasasi Farmers Self Help Group wrote to the Chairperson of the National Land Commission, expressing concerns over the construction of the road linking Lamu Port to Kwasasi which has destroyed farms belonging to Kwasasi farmers. Kwasasi Farmers Self Help Group requested that monetary compensation be paid to affected farmers for the land and crops destroyed. No response from the National Land Commission was received.

-

Aug 2018

Kwasasi Farmers Self Help Group wrote to the Ministry of Transport. This letter expressed concerns over the construction of the road linking Lamu Port to Kwasasi, which have destroyed farms belonging to Kwasasi farmers. Kwasasi Farmers Self Help Group requested that monetary compensation be paid to affected farmers for the land and crops destroyed. No response from the Ministry of Transport was received.

-

Jun 2018

Save Lamu wrote to Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) notifying that they have sent a request for information to ICBC regarding the bank’s investment in the Lamu coal plant. No response from ICBC was received.

-

May 2018

Accountability Counsel and Save Lamu traveled to Abidjan for the AfDB’s Civil Society Forum, where we engaged with the bank’s board members regarding continued inadequacies in the environmental and social impact assessment for the Lamu Coal Plant.

-

Dec 2017

Save Lamu wrote to Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) reiterating concerns over the proposed coal plant, and the project’s violations of the Green Credit Guidelines in which Chinese banks are obligated to follow. Due to these serious concerns, Save Lamu recommended that ICBC withdraw its financing of the project. No response from ICBC was received.

-

Nov 2017

Save Lamu sent detailed comments to the African Development Bank calling attention to the many gaps and inadequacies in the environmental and social impact assessment for the Lamu Coal Plant. Days after the letter was sent, we received notice that the planned AfDB Board vote on approval of a partial risk guarantee for the project had been removed from the Board meeting agenda. It remains on hold.

-

Dec 2016

Save Lamu wrote to Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) raising concerns over the proposed coal plant, and highlighted the project’s violations of the Green Credit Guidelines in which Chinese banks are obligated to follow. Save Lamu requested ICBC to consider delaying any financing to the project until Amu Power has completed its due diligence in fully investigating the potential of renewable energy alternatives. No response from ICBC was received.

-

Nov 2016

Upon receipt of Save Lamu’s appeal, NET issued a stay order, halting development of the proposed coal plant during the Tribunal’s proceedings.

-

Nov 2016

Save Lamu files an appeal with Kenya’s National Environmental Tribunal (NET) challenging NEMA’s decision to grant the EIA license to Amu Power for the coal plant.

-

Oct 2016

Save Lamu and Natural Justice submitted an objection to Kenya’s Energy Regulatory Commission regarding NEMA’s EIA license for coal plant. This objection included a report by former ERC Chair, Mr. Hindpal Singh Jabbal, advising that the coal plant cannot be justified given “technical, economic, site location, social, and environmental considerations.”

-

Sep 2016

NEMA granted an Environmental Impact Assessment License for the Lamu Coal Plant just days after receiving extensive comments on the proposed project during the required public comment period.

-

Aug 2016

Save Lamu submited comments to the National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA) of Kenya, critiquing the factually inaccurate and incomplete ESIA Study Report. Under Kenyan law, NEMA is the agency responsible for deciding whether or not to grant an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) license for the coal plant.

-

Jul 2016

IFC responded to Save Lamu’s letter, stating that the IFC does not have exposure to the plant through any of the financial intermediaries mentioned.

-

Jul 2016

Kurrent Technologies, Ltd., a consultant appointed by Amu power, completed and published an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) Study Report on the proposed coal plant.

-

Apr 2016

Save Lamu wrote to International Finance Corporation (IFC), highlighting concerns about the potential involvement of the IFC in financing the proposed coal plant through a financial intermediary.

-

Mar 2016

Save Lamu wrote to Amu Power expressing concerns about the lack of meaningful community consultation and participation in the design of the coal plant, and the lack of due consideration given to the high environmental, social, and cultural risks of the project. Save Lamu requested that the design of the coal plant is not finalized, and that construction does not begin until community concerns have been addressed. No substantive response from Amu Power was received.

-

Dec 2015

AfDB responded to Save Lamu’s letter suggesting that Save Lamu communicates future concerns to Amu Power directly to allow them the opportunity to engage directly with the concerned communities and families.

-

Nov 2015

Save Lamu responded to the AfDB, highlighting additional concerns about the Lamu Coal Plant, including major flaws in the Environmental Project Report (EPR) and the threat of imminent displacement of local communities.

-

Nov 2015

Kwasasi farmers wrote to Lamu County Land Management Board objecting to the intention of titling 869 acres of land in Kwasasi to Amu Power for the Lamu coal plant, arguing that the land should be classified as “Community” land, with farmers recognized as the rightful owners.

Save Lamu also objected to the National Land Commission’s notice of intention to transfer the land to Amu Power. The transfer would have had the effect of displacing local communities who have farmed the land for generations.

-

Nov 2015

With Accountability Counsel’s support, Save Lamu provided a detailed critique of the EPR for the coal plant. This report failed to comprehensively assess the project’s environmental and social impacts and did not detail any mitigation strategies. It also did not constitute a full Environmental and Social Impact Assessment, which AfDB policy requires.

-

Nov 2015

AfDB responded to Save Lamu’s letter with an assurance that the Bank would conduct a careful review of the coal plant’s environmental and social impacts.

-

Oct 2015

Accountability Counsel supported Save Lamu’s letter to AfDB Management expressing concerns about the high environmental, social, and cultural risks of the project and about the lack of community consultation and participation to date. Save Lamu requested: a comprehensive ESIA, further feasibility investigation, and more meaningful community consultations, all with the objective of securing the local community’s free, prior, and informed consent to the project.

Save Lamu subsequently met with AfDB representatives to express their concerns in person.

-

Oct 2015

An Environmental Project Report was released for comment.

It was a preliminary environmental report required under Kenyan law as a step toward granting an environmental license for the project. The EPR failed to comprehensively assess environmental and social impacts and did not detail any mitigation strategies.

-

Jul 2015

Save Lamu wrote to international non-government organizations requesting support for a petition to halt the construction of the proposed coal power plant.

-

Jun 2015

Save Lamu wrote to the Kenyan National Environment Management Agency, the government agency responsible for issuing an environmental impact license for the project. This letter expressed communities’ initial concerns about health, safety, and environmental impacts of the coal power plant and about the inadequacy of the public information sessions.

-

Apr 2015

UNESCO published a report on its Reactive Monitoring Mission to Kenya which was triggered by LAPSSET’s likely negative impact on Lamu Old Town, a World Heritage Site. The report raises specific concerns about the negative environmental and social impacts of the proposed coal plant.

-

-

Impact

For many years, local communities have been speaking out and raising concerns about the Lamu coal-fired power plant, which threatens to severely disrupt their environment, and cause devastating impacts on their health, livelihoods, food security, and cultural heritage. Lamu communities have organized themselves under collectives such as Save Lamu and the Kwasasi Mvunjeni Farmers Self-Help Group to make their voices heard.

However, the lack of adequate and meaningful response from international investors of the project, including the non-responsiveness of Chinese and other financiers, has led to communities feeling increasingly frustrated and ignored.

As a result, Save Lamu and the Kwasasi Mvunjeni Farmers Self-Help Group requested Accountability Counsel’s support to develop and pursue a complaint strategy targeting international investors. Accountability Counsel worked with international partner Inclusive Development International to identify obscure but critical financial links to the International Finance Corporation (IFC). Accountability Counsel also worked with community groups to document the harm Lamu communities are already experiencing, and the future harm they fear, in a detailed complaint to the IFC’s accountability office, the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO). A summary of the complaint is available in English and Kiswahili.

Complainants requested that the CAO conduct an investigation into the potentially disastrous project. In July 2019, however, the CAO found the complaint ineligible, determining that the links to the IFC did not constitute active, material exposure to the project. The decision was especially disappointing in that it confirmed a pattern of IFC support for the project, such that the complaint may have been eligible had it been filed at an earlier point in time. The lack of transparency regarding the IFC’s financial intermediary links to problem projects, like the Lamu coal plant, make it difficult, if not impossible, for complainants to know in advance whether such complaints will be eligible.

The complaint is the continuation of many years of collaboration between Accountability Counsel and Save Lamu that has created impact on both a national and international scale. At an earlier stage, our work influenced the African Development Bank (AfDB) to delay consideration of support for the Lamu coal plant. Together with local and international partners, Accountability Counsel exposed significant flaws in the environmental and social review process for the coal plant, and we informed the AfDB’s staff, leadership, and other key investors of these deficiencies. The AfDB’s approval of a partial risk guarantee for the project remains on hold, in part because of these deficiencies in the environmental and social review process.

After the success of pressuring the ICBC and its investors to withdraw from the project, together with Save Lamu, the Kwasasi Mvunjeni Farmers Self-Help Group, Natural Justice, and other partners, our focus remains to continue to pressure investors and other key stakeholders to divest from this harmful project.

-

Case Media

Videos

Press Releases

- 16 November 2020 ICBC withdraws financing from the Lamu Coal Plant By Khadija Shekuwe, Save Lamu

Blog Posts

- 10 December 2024 Guardians of Lamu: A Community’s Journey to Protect Land and Heritage / Walinzi wa Lamu: Safari ya Jamii Kulinda Ardhi na Urithi wao By Accountability Counsel and Save Lamu

- 23 September 2020 Transparency of Financial Sector Investments Should be a Priority for IFC Reform Process: Save Lamu

- 30 October 2019 Shifting Risk from the Poor to the Powerful Through Accountability: 2019 World Bank Group Annual Meetings Read Out By Accountability Counsel

- 2 September 2019 IFC Escapes Responsibility for Lamu Coal Plant Contributions

- 24 May 2017 Escalating Threats in Lamu, Kenya Interfere with Local Communities’ Right to Public Participation

- 5 October 2015 Communities in Lamu, Kenya Object to AfDB’s Role in Planned Coal Power Plant

Op-Eds

- 12 June 2019 China’s promise of responsible belt and road investments is in the hands of its bankers Natalie Bridgeman Fields, Accountability Counsel, in South China Morning Post

- 11 December 2018 Protecting Communities’ Rights in Africa: Reflections on the 2018 ACCA General Assembly By Stephanie Amoako, Accountability Counsel, in African Coalition for Corporate Accountability

- 3 February 2018 China Moves Toward Accountability for Overseas Financing

Media Coverage

- 29 June 2021 Biggest China Bank Abandons $3 Billion Zimbabwe Coal Plan By Ray Ndlovu and Antony Sguazzin, Bloomberg

- 13 November 2019 African Development Bank decides not to fund Kenya coal project By Alexander Winning, Reuters

- 11 July 2019 Kenya’s first coal plant construction paused in climate victory By Karen McVeigh, The Guardian

- 21 June 2019 Planned coal plant blackens the mood in Kenya’s idyllic Lamu By France 24

- 13 June 2019 It’s time to scrap Lamu coal plant By Star Editor, The Star Kenya

- 11 June 2019 After SGR, Kenya’s next Sh900bn debt trap for power project By Allan Olingo, Nation

- 10 June 2019 Kenya Coal Plant’s Power Could Cost 10 Times More Than Suggested, Group Says By David Herbling, Bloomberg

- 9 June 2019 When Coal Comes to Paradise By Dana Ullman, Foreign Policy

- 4 June 2019 Row over Chinese coal plant near Kenya World Heritage site of Lamu By Alastair Leithead, BBC News

- 15 August 2018 2018 Revealed Just How Ill-Prepared We Are For Climate Change By Terry Gross, NPR, with Somini Sengupta, New York Times

- 9 April 2018 At what cost will Lamu coal power plant be to Man and sea? By Jacqueline Kubania, Nation

- 27 February 2018 Why Build Kenya’s First Coal Plant? Hint: Think China By Somini Sengupta, New York Times

- 26 January 2018 Lamu coal plant to cost power users Sh37bn yearly By Neville Otuki, Business Daily Africa

- 23 May 2017 Lamu port project has denied us cultural rights, fishermen tell court By Charles Lwanga, Nation

- 10 May 2017 As the World Cuts Back on Coal, a Growing Appetite in Africa By Jonathan W. Rosen, National Geographic

- 5 January 2017 Kenyans at loggerheads over coal plant at world heritage site By Daniel Wesangula, Thomson Reuters Foundation

- 28 August 2015 In Kenya, Proposed Coal-Fired Power Plant Threatens World Heritage Site By Nicole Ghio, HuffPost

- 12 July 2015 Expert says coal plant bad for health By Eunice Kilonzo & Kalume Kazungu, Nation

- 1 November 2014 In Kenya, islanders on heritage site count cost of $25 billion mega-project By Jason Patinkin, The Christian Science Monitor

- 19 August 2014 Violence Imperils Kenya Port Project By Heidi Vogt, Wall Street Journal

- 15 April 2014 Kenya: Oil metropolis threatens coastal paradise By Oxpeckers

- 24 February 2014 Pastoralist aspirations versus policy in the Horn of Africa By IRIN

- 9 October 2013 Livelihood concerns as Kenya kicks off regional infrastructure project By IRIN

- 31 October 2012 Disquiet over Lamu port project By IRIN

- 5 June 2012 Group seeks new bench for Lamu Port petition Sandra Chao, Nation

- 25 April 2012 Kenya Parliament pushes for faster completion of Lamu port link By Edwin Mutai, Business Daily Africa

- 15 April 2012 Toyota proposes to build Lamu to South Sudan pipeline By Giffins Omwenga, Nation

From Our Partners

12 April 2018

12 April 2018The UN Environment Programme published an opinion article by our local partners DeCOALonize, sharing local perspectives on the feared social and environmental impacts of the Lamu Coal Plant.

Photos

-

Marine biodiversity and traditional livelihoods are threatened by the Lamu coal plant

Marine biodiversity and traditional livelihoods are threatened by the Lamu coal plant -

Square outside the Old Fort in Lamu. Lamu Old Town is recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Square outside the Old Fort in Lamu. Lamu Old Town is recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. -

A traditional fisherman in Lamu. The proposed coal plant existentially threatens Lamu’s two most important economic activities: fishing and tourism

A traditional fisherman in Lamu. The proposed coal plant existentially threatens Lamu’s two most important economic activities: fishing and tourism -

Two farmers in Kwasasi. 109 farmers in Kwasasi have already been displaced by the Lamu coal plant access road.

Two farmers in Kwasasi. 109 farmers in Kwasasi have already been displaced by the Lamu coal plant access road. -

Traditional fishing boats in Lamu Old Town. The Lamu coal plant would damage marine ecosystems, threatening fisherfolks' livelihoods.

Traditional fishing boats in Lamu Old Town. The Lamu coal plant would damage marine ecosystems, threatening fisherfolks' livelihoods. -

Mohamed Shee, a farmer-fisherman in Kwasasi. 109 farmers in Kwasasi have already been displaced by the Lamu coal plant access road.

Mohamed Shee, a farmer-fisherman in Kwasasi. 109 farmers in Kwasasi have already been displaced by the Lamu coal plant access road. -

LAPSSET coalition training (credit: Desiree Koppes)

LAPSSET coalition training (credit: Desiree Koppes) -

Abubakar M. Ali Almoudy, Chairman of Save Lamu (credit: Desiree Koppes)

Abubakar M. Ali Almoudy, Chairman of Save Lamu (credit: Desiree Koppes) -

Hadija during LAPSSET coalition training.

Hadija during LAPSSET coalition training. -

The proposed coal plant existentially threatens Lamu’s two most important economic activities: fishing and tourism.

The proposed coal plant existentially threatens Lamu’s two most important economic activities: fishing and tourism. -

Save Lamu session. Lamu communities are calling on investors to divest from Lamu coal.

Save Lamu session. Lamu communities are calling on investors to divest from Lamu coal. -

The site of the proposed Lamu coal-fired power plant.

The site of the proposed Lamu coal-fired power plant.