New Report, Our Last and Only Resort, Examines What Happens When Development Goes Wrong in the Middle East and North Africa

In early 2010, farmers in the Chichaoua region of Morocco noticed a slew of environmental problems impacting their land. Their drinking water had become dirty and discolored, their homes were cracking, farmlands eroded, and water streams and traditional dams were damaged. The culprit: the Marrakech-Agadir Motorway, a large, internationally funded highway project that was under construction near their farmland.

A civil society organization operating in the area, the Center for Development of the Region of Tensift in Morocco (CDRT), knew that the African Development Bank (AfDB) contributed funding to the motorway project. Further, CDRT knew that the AfDB contained within it an “independent accountability mechanism”, or IAM, where communities could file official complaints about harm caused by AfDB-financed projects in an effort to remedy damage. CDRT filed a complaint on behalf of the affected communities to the AfDB’s IAM: the Independent Review Mechanism (IRM). While an agreement was ultimately reached, the process was rife with complications. The process took five years from the time CDRT filed the complaint with the AfDB IRM until an agreement was signed. CDRT President Dr. Ahmed Chehbouni reflected, “We waited 5 years before they gave us a single centimeter.” In addition to the extensive time, CDRT and the affected communities faced other complications, including contributing substantial financial resources in order to get to meetings without reimbursement, facing retaliation by the AfDB and project authorities (including being blacklisted by authorities for raising a complaint), being required to translate their complaint and materials into English, and others. When CDRT was approached about supporting another community through a similar complaint process, Dr. Chehbouni politely declined, saying, “We’re tired. We won’t take it up because we’re exhausted.”

Our new report Our Last and Only Resort: What Happens When Development Goes Wrong in the Middle East and North Africa? co-authored by Accountability Counsel and the Arab Watch Coalition, reflects exactly the sentiment Dr. Chehbouni expressed. The report draws on over 20 years of complaint and project data across the region, and first-hand accounts from nearly a dozen communities across five MENA countries. Through our research, we found that communities in the MENA face disproportionately severe limitations on access to accountability and remedy from harm.

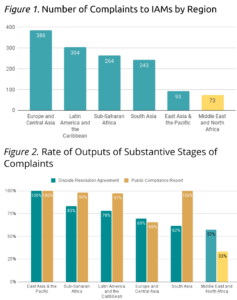

The MENA region has the fewest complaints to IAMs, and extremely low rates of those complaints reaching outputs from the process (see Figures 1 and 2). In an effort to understand why this trend persists, we spent months investigating why complaints in this region fall short and what can be done to improve accessibility and efficacy of IAMs for impacted communities, in the MENA and beyond.

Our research indicates that one likely reason for this disparity in complaints is that none of the development banks operating in the region that have an IAM are actually headquartered there. International financial institutions (IFIs) like the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) operate purely as foreign actors in the region. These IFIs and their IAMs often lack local language capacity to accommodate communities, and have limited information available to communities on how to access IAMs. Other barriers to access such as IAM language requirements for communities facing harm to submit complaints in English or French also appear to be limiting the number of complaints. We found that while eight out of 12 active IAMs explicitly accept complaints filed in any language, the other four (representing 42% of all complaints filed in the MENA) do not.

When communities facing harm do engage with IAMs, they face several major barriers, chief among them the risk of reprisal against those who speak out. Local governments and government-backed private actors receiving funding from IFIs often intervene in the institutions’ favor by suppressing popular protests against development projects. Following conversations with local activists and community groups, our report notes that any challenge to IFI financing, such as raising a complaint with an IAM, can be perceived as a direct attack on the state.

While retaliation against communities engaged in the complaint process is a sad reality across the globe, the disparate complaint statistics and interviews with groups filing complaints in the MENA region suggest that retaliation is particularly common in this area of the world. Nearly all of the groups we interviewed mentioned that retaliation was of high concern to advocates and community members. One group interviewed recounted the response by the government, before and after they filed their complaint to the IAM:

“The day we started voicing our concerns, we were met with accusations of treason and working with enemies of the state, which was threatening. We didn’t feel at any point that there was a place to discuss our concerns with the government. After the complaint was filed, security forces and the national army were on site. They intimidated us in many ways, and summoned us for interrogation about our social media posts.”

This dynamic is exacerbated by IFIs themselves, whereby the transfer of large sums of money to government ministries can be perceived as conferring legitimacy upon those bodies. However, that also means that IFIs have ample leverage to challenge political and social repression in the MENA region. For starters, we recommend that these institutions make project financing contingent on delivering remedy for past abuses and addressing prior noncompliance on the part of state institutions. We also recommend that IFIs and IAMs adopt zero tolerance policies related to reprisals, and develop clear guidance, protocols, procedures, and regular training for staff.

Even when IAM processes do result in agreements and public compliance reviews, the implementation of those commitments is challenging, and remedy has proven extremely rare for communities in the MENA. Oftentimes, the remediation of findings of non-compliance relies on the IFI acting in good faith: “even though the investigation was a direct result of the complaint, the proposed solutions were non-obligatory decisions. The bank could implement them or not implement them” (YOHR). IAMs and IFIs have a responsibility to ensure that findings of non-compliance are addressed, and agreements are implemented. To ensure real remedy is reached, we recommend IFIs utilize existing leverage points, such as requiring clients to engage in IAM processes, withholding project payments and disbursement of funds during ongoing complaints, and conditioning new funding from IFIs on the provision of remedy for prior harm.

Development institutions have a unique opportunity to provide tangible benefits for some of the world’s most vulnerable communities. The surest way for a development project to miss its mark, however, is to fail to heed these very communities. Unfortunately, a refusal to acknowledge local people as key stakeholders in development projects has been the norm in the MENA. “The government does not really deeply acknowledge civil society. They give them a license to operate but don’t really recognize them as partners. We know that the participation of civil society is very important for not only transparency and rights, but also enhancing the outputs of development” (Yemen Observatory for Human Rights). We know that IAMs are most effective when they are accessible, accountable, and have the ability to provide real outcomes for communities. Providing an effective channel for communities to raise concerns and lead project development could mean the difference between achieving intended project outcomes with minimal harm and replicating the colonial violence that has plagued the MENA region for decades.

Our report is available online at lastandonlyresort.com, and available in downloadable pdf format here. We hope the findings from this report shed light on the existing barriers communities face when seeking justice through accountability mechanisms and provide clear direction for IFIs and IAMs to address these barriers. We also hope that this report inspires future investigations into factors required to understand and improve the accountability ecosystem in international finance.