The Need for Human Rights Commitments and Assurances in Development Finance – A Letter to Finance in Common Participants

The second week of November 2020 marks the first ever convention of “public development banks” concerned with the health and economic crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as with achieving sustainable development objectives. Called the Finance in Common Summit, the event is intended to coalesce the agendas of banks, governments, and other stakeholders to prioritize sustainable recovery measures and push finance toward a “future we want.” But who is included amongst “we”?

It is essential that any sustainable development strategy respect the rights of communities that bear the most risk of unintended investment impacts. This is why well in advance of the Summit we joined over 200 civil society organizations to urge that human rights be reflected in the core agenda, and that key deliverables include commitments to abide human rights principles and community empowerment. Of great disappointment, the Summit proceeds without any dedicated space for meaningful dialogue on safeguarding the human rights and participation of communities in development.

Without due consideration of the human rights impacts of projects intended to provide aid and development, public development banks will simply fall short of the Summit’s aspirations. Data from the independent accountability mechanism of major development finance institutions make this abundantly clear. We have released the below public statement that shares this data and once again urges Summit attendees to prioritize commitments to human rights and respecting community voices in development. To finance the future we all want, development banks must embrace accountability mechanisms as an effective way to ascertain and remedy unintended adverse project impacts.

The Data Speaks: Sustainable Recovery Goals Risk Falling Short Without Respect for Human Rights

As the world’s public development banks (PDBs) prepare to convene at the Finance in Common Summit to coordinate prerogatives in responding to the COVID-19 and global climate crises, human rights and community voices must be at the center of the decisions. There is simply no way to achieve just and equitable solutions to global challenges without due consideration of the human rights impacts of projects intended to provide aid and development. This lesson has been repeated many times over in the context of development finance.

Many international finance institutions (IFIs) have installed independent accountability mechanisms (IAMs) to assure that investments measure up to development goals and do not violate the respective social and environmental policies aimed at achieving those goals. Communities affected by investment projects rely on IAMs to raise concerns; where communities often have no other means for recourse, IAMs provide a venue to prevent, mitigate, and remedy harm by course-correcting non-compliance with institutional safeguards and policies. Not only are IAMs an effective way to understand on-the-ground project impacts, but the complaints submitted to IAMs provide important data for understanding the social and environmental risks of investments across all regions and sectors. An analysis of IAM cases demonstrates that international financial flows risk harming individuals’ human rights and that investors learn of these risks by hearing directly from project-affected communities.1

Important lessons from development finance

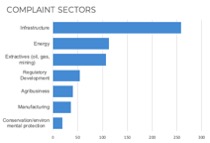

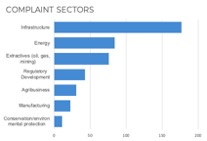

Complaints to IAMs often allege serious environmental and social harm, including but not limited to inadequate due diligence, consultation, and disclosure, environmental damage, increased pollution, physical and economic displacement, loss of livelihood, disruption of cultural heritage, compromised community health and safety, gender-based violence, gender discrimination, violence against communities, and retaliation or reprisals against journalists, environmental activists, and human rights defenders.2 Development finance projects risk causing harm globally and in nearly every sector: complaints arise from projects located in over 120 countries and pertain to infrastructure, agriculture, energy, extractives, capacity-building, manufacturing, and regulatory projects, among others. In fact, the vast majority of eligible IAM complaints that concern human rights violations relate to investments into infrastructure and energy projects, the very sector investments envisioned by the Summit to accelerate climate adaptation and resilience (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Sector projects most frequently the subject of eligible complaints

Figure 2: Sector Projects most frequently the subject of eligible complaints concerning human rights violations

Of the 1,262 disclosed complaints that allege noncompliance with environmental and social standards, 508 were deemed eligible to continue with an IAM process, which can include compliance investigation and/or dispute resolution. Approximately seventy-five percent (75%) of all eligible complaints that undergo a compliance investigation reveal non-compliance with bank policies meant to safeguard against environmental and social harm. Compliance investigations of eligible complaints concerning potential human rights violations have yielded findings of non-compliance more than eighty percent (80%) of the time (see Figure 3). When considering only those complaints that explicitly reference the term “human rights” to describe the extent of harm, the rate rises to over ninety percent (90%) (see Figure 4).

Figure 3: Eligible complaints with human rights implications that have undergone a compliance review revealing non-compliance

Figure 4: Eligible complaints explicitly referencing violations of international human rights that have undergone a compliance review revealing non-compliance

Respect for human rights and adequate due diligence make the difference between good intentions and bad impacts.

The importance of protecting human rights through community feedback and accountability is true for projects with explicit impact goals, including crisis response. Even the most well-intended projects can produce unanticipated harm that become fully known to investors only after communities used IAMs to voice their grievances. Take, for example, a biomass project in Liberia with the stated project goal of advancing renewable energy in a country rebuilding after years of devastating conflict. In reality, the project caused deforestation, sent family farmers and other subsistence producers into poverty, and contaminated water resources, amid sexual abuse and labor rights violations. Take, as another example, a hydroelectric project in Mexico that was intended to produce renewable energy, unfortunately commenced through illegal land acquisitions. All of the energy generated by the project would have been sold to private companies, but communities bore all of the risk, including harm to local water supply and compromised safety of an adjacent dam curtain. When investors learned of these impacts due to communities’ use of an accountability office, they ultimately decided that the project was untenable. In both cases, investors believed that they were benefiting their host communities. Yet it took hearing from those communities through IFI accountability office processes to understand the catastrophic financial, human, and environmental outcomes.

Unfortunately, and at the risk of undermining the effectiveness of sustainable recovery measures, many financial institutions and investors attending the Finance in Common Summit are not equipped with the mechanisms needed to receive community feedback and address risks to human rights when they arise. It is therefore imperative that the Summit provide a platform to properly instruct institutions on the social and environmental standards needed to meet the moment and the governance tools needed to prevent and address harm to communities.

Conclusion

No matter the intentions, PDBs simply will not be able to coalesce around a just, equitable, and sustainable recovery without prioritizing individuals’ human rights. This is why global communities and civil society are demanding that respect for human rights be ingrained in each event at the Finance in Common Summit, including a session dedicated to the topic specifically. Further, any collaborative development initiatives agreed to at the Summit must ensure that effective accountability mechanisms are available to respect the human rights of communities potentially impacted by investment projects, as according to Principles 30 and 31 of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. We therefore urge Summit organizers and participants to prioritize commitments to human rights and respecting community voices in development.

Footnotes

[1] Accountability Counsel has developed a new tool called Accountability Console, which includes a comprehensive database of all disclosed complaints submitted to the independent accountability mechanisms of major development finance institutions. Available at www.accountabilityconsole.com.

[2] At least sixty-five percent (65%) of all complaints found eligible by the IAMs of major development finance institutions (343 out 508 total eligible complaints) have alleged adverse project impacts that implicate potential human rights violations. A document search reveals that forty-seven (47) complaints from the same pool explicitly use the term “human rights” to allege human rights violations. These amounts do not include valid human rights concerns raised in complaints deemed ineligible for technical or unknown reasons.

[3] Compliance Investigation is a review by an IAM into whether an IFI followed the relevant environmental and social safeguard policies in its administration of the project that is the subject of a complaint. As a part of a compliance investigation, the IAM publishes a report with findings regarding the IFI’s compliance with relevant policies.

Related Posts

- 24 September 2020 Amplifying Community Expertise

- 22 September 2020 To reduce climate change learning curve, philanthropists lean on collaboratives

- 31 August 2020 Accountability Counsel: Advocating for People Harmed by Internationally Financed Projects

- 31 August 2020 Co-financed Projects Demonstrate the Accountability Gap of Certain Impact Investments