Understanding Community Harm Part 6: Cultural Heritage

Individuals, communities, and NGOs file complaints to international finance institutions (IFIs) for harm caused by IFI-funded development projects. In compiling these complaints into the Accountability Console database, our research team tries to ascertain and categorize the issues or concerns raised for each complaint. Of all these complaints, six percent detail impacts on any type of tangible or intangible cultural heritage, including harm to significant sites, unique environmental features, cultural knowledge, or traditional lifestyles. Comparing the 97 cultural heritage complaints to the entire known universe of 1,614 complaints highlights how much harm even one project can create on entire communities.

Case Study: Cultural heritage in India’s Jharkhand Water Project

Cultural heritage can include sacred sites that sometimes contain hundreds of years of cultural reverence and local negotiations with other communities. These communities often precede the formation of IFIs by multiple generations yet must rely on the IFIs’ independent accountability mechanisms to seek remedy. One recent example of such a site threatened by international development exists in Jharkhand, India.

The World Bank-funded Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Project for Low Income States committed $500 million “to improve piped water supply and sanitation services for selected rural communities” in India. When multiple Indigenous groups protested against the project — including women and children — police responded with force. The community turned to the Inspection Panel, the accountability mechanism of the World Bank, to file a complaint. The Inspectional Panel received two separate requests for inspection but processed them jointly (see first and second requests). The joint complaint concerns the infrastructure and regulatory development sectors with five complaint issues: consultation and disclosure, due diligence, cultural heritage, environmental harm, and livelihoods.

The complainants identify themselves as the Adivasi (Indigenous or original inhabitants) community of Neecha Tola, Purana Basti, in Sarjamda village in East Singhbum district of the state of Jharkhand, India. Economically, the community cited fear of further impoverishment caused by having to pay for water that had been available free of charge prior to the project. Culturally, construction began on community land, locally called Romantic Ground or Gota Tandi. The Romantic Ground is home to annual Gota Pooja celebrations, a Jaher Dungri ceremony every five years, and an annual martyrdom day. Construction on the project not only displaced a cultural heritage site, but also destroyed sacred artifacts. The boulders, marking the struggle of three boys for Jharkhand statehood, were replaced with a statue to which the community never consented.

First appearing for a soil assessment in 2015, the District Water and Sanitation Department (DWSD) returned in April 2016 with machinery but community protests halted construction. The DWSD promised that they would not begin construction without a resolution from a Gram Sabha, or village general assembly. Yet in December 2016 the construction began while “traditional leaders from Neecha Tola were in Delhi to participate in a program on traditional governance,” as stated in their original complaint.

By March 2019, the Inspection Panel began their investigation, submitting it for World Bank Board of Directors approval in January 2020. The Inspection Panel finally released the report in February 2021, admitting that complaints from Giddhijhopri and Sarjamda Purana Basti typify failings plaguing hundreds of water schemes funded under the project. In August 2021 the Inspection Panel reported that “the consultation process has been delayed due to COVID-19 and the investigation process is still ongoing at the time of this ICR Review (June 2021).” Unfortunately, the Adivasi are still awaiting remedy eight years later.

Understanding the Complaint Universe

As with the Jharkhand water project, cultural heritage complaints can include harm to both tangible (e.g. significant sites or unique environmental factors) and intangible (e.g. cultural knowledge and traditional lifestyles) aspects of life. In comparison to the entire known complaint universe, where 45.2% of all complaints are about infrastructure projects, 63% of cultural heritage complaints involve infrastructure. In other words, many of these complaints directly link material projects and practices to sometimes intangible practices of cultural heritage, often highlighting other issues in the process.

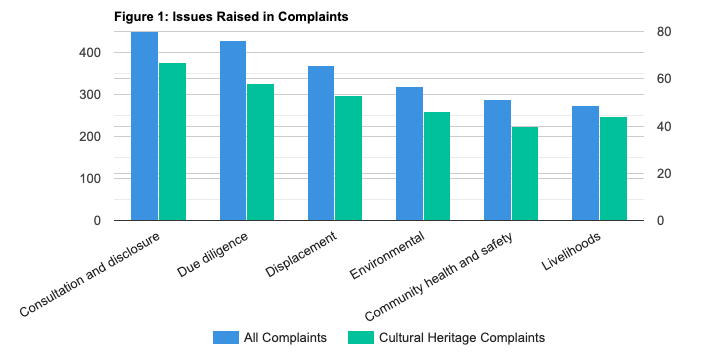

For example, 27.9% of all complaints in the Console concern consultation and disclosure, followed closely by due diligence at 26.6%, then by displacement at 23%. However, just like complaint sectors, complaint issues are not mutually exclusive. In this case, cultural heritage complaints are 400% more likely to also raise Indigenous People’s issues and 99% of cultural heritage complaints raise at least one other concern, such as environmental, water, or biodiversity issues.

Regardless of complaint issue, the majority of all complaints are filed in three regions: Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Sub-Saharan Africa. The majority (31%) of cultural heritage complaints are filed in Latin American and the Caribbean, comprising 18.8% of the region’s 304 complaints.

After filing the initial complaint, the complainant must choose between dispute resolution or compliance review. Complainants can pursue both options in some independent accountability mechanisms, but the processes occur sequentially. Of the 1,614 complaints to date, 10.9% have proceeded to dispute resolution and 17.3% proceeded to compliance review. Of the complaints which proceeded to dispute resolution, 56.8% have reached an agreement, while 75.3% of those which proceeded to compliance review produced a compliance report. Complaints raising cultural heritage issues follow this same trend, with 17.5% proceeding to dispute resolution and 56.3% reaching an agreement. Where cultural heritage complaints differ is that 40.2% led to compliance review with a 76.9% producing a compliance report.

Moving Forward

Looking at quantitative data alone only gives us a glimpse into how communities respond to cultural heritage harm. But taken together with the Jharkhand case and many others, we see how Indigenous communities use accountability mechanisms to hold governments and corporations accountable. Given that the Inspection Panel report referenced above stated that the project failings typify hundreds of water schemes, which other communities might have been harmed but did not file complaints? And what does a successful compliance review investigation mean if communities still do not have remedy after eight years, such as the Adivasi community fighting the Jharkhand water project in India?

We, as advocates, must continue to think about what happens when these accountability mechanisms produce findings and recommendations but do not provide meaningful remedy to communities facing harm. How much harm could the World Bank and other IFIs institutions prevent instead of apologizing for by truly prioritizing consultation, disclosure, and due diligence? How much harm could be avoided if development finance institutions required that all clients and subclients be told about accountability mechanisms? And how do we, as advocates, best serve those harmed in seeking remedy? And if banks know1 that they do not have strong political, social, or monetary consequences for clients and subclients who intentionally or unintentionally disregard safeguards, what would it take to change that?

I do not have any answers yet, but I hope to work with partners to build a future where real remedy is possible.

Endnotes

1. See Results and Performance of the World Bank Group 2018 Appendices. Page 209-210 on safeguard outcome documentation; p. 223-28 “Engaging Citizens for Better Development Results”; p. 237 footnote 36; p. 240 footnote 76; p. 242 footnote 88, 90, 91, 92, 93, and 96; and p. 170, quoted at length: “In other cases, implementation deficiencies were recorded, but these varied widely, and it is not always clear why an MS rating was chosen instead of a lower rating. The descriptions of these deficiencies ranged from reporting on “health and safety concerns, leading to the unnecessary and preventable loss of lives and properties in the project contracts” in an Ethiopian road project, to a “lack of proper cleaning of a river bed from construction waste” in Georgia, to a “lack of reporting on the status of the Resettlement Action Plan” in an African regional project.”

This article was originally published in the Accountability Console Newsletter, where AC’s Research team shares research and insights from the world’s most comprehensive database of Independent Accountability Mechanism (IAM) complaints, the Accountability Console. Click here if you would like to subscribe to the monthly Console Newsletter. To read the rest of the Understanding Community Harm series, click here: livelihoods, gender-based violence, displacement, environmental impacts, consultation, disclosure, and due diligence.