The Eligibility Bottleneck

Understanding the reasons why complaints fail to advance beyond preliminary stages allows visibility into the system of accountability in international finance, and helps us evaluate how IAMs are functioning as sources of redress for communities facing harm.

The Lamu coast in Kenya is home to indigenous communities, coastal mangrove forests, fishers, farmers, and a UNESCO-recognized World Heritage site. It is also now the source of a proposed 1,050 MW coal-fired power plant, a US$2 billion project being developed by Amu Power, a joint enterprise of Kenyan firms Gulf Energy and Centum Investment. If constructed, the project would have grave impacts to local communities, including loss of land and livelihoods, pollution of air, water, and land, and a decline in marine resources. In April of 2019, two community groups, Save Lamu and the Kwasasi Mvunjeni Farmers Self-Help Group, filed a complaint to the International Finance Corporation’s accountability office, the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO). The complaint raises concerns about serious violations of the IFC’s Performance Standards in the development of the proposed coal plant. Complainants requested that the CAO conduct an investigation into the potentially disastrous project. In July 2019, however, the CAO found the complaint ineligible, determining that the links to the IFC did not constitute active, material exposure to the project.

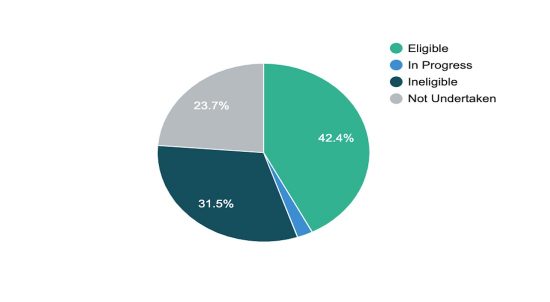

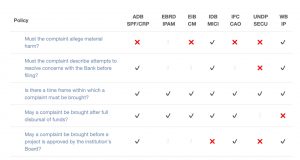

Communities in Lamu facing harm from an internationally financed project are one of many instances of grievances filed to Independent Accountability Mechanisms (IAMs) that go unaddressed. Before an IAM will agree to devote the resources to addressing a grievance, it usually must pass through two preliminary stages: registration and eligibility. While individual IAMs vary in their exact processes, registration and eligibility stages are generally designed to confirm the complaint contains an allegation of harm from a bank-funded operation and meets the submission requirements and criteria to proceed. Specific eligibility criteria vary by mechanism, and range quite widely. Only once a complaint is deemed “eligible” can it proceed to a substantive stage of the accountability process, Compliance Review or Dispute Resolution.

However, the majority of complaints never make it past eligibility; to date, only 42% of complaints have been deemed eligible to proceed to a substantive stage of the complaint process.

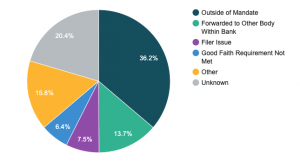

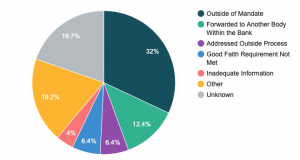

The most common reason cited for ineligibility is unknown, meaning that the IAM has not publicly disclosed any justification or information regarding its determination. When an IAM fails to make the reasoning behind its eligibility determinations publicly available, it undermines commitments to transparency and accessibility.

The next most common reason for ineligibility is that a complaint falls outside of the IAM’s mandate. Most IAMs are mandated only to address grievances that relate to social or environmental harm; some complaints fall into this category because they do not relate to community harm, and instead raise issues related to fraud, corruption, or procurement. These complaints may be forwarded to other bodies within the bank that are mandated to deal with such issues. However, when further information is not disclosed, it’s impossible to verify whether these issues are in fact being addressed, or even if they were properly forwarded in the first place. This lack of transparency also makes it difficult to know what specific aspects of the complaint fall outside of the mechanism’s mandate.

Another common reason for ineligibility is the tight timeline for communities to file a complaint. Typically, complaints can’t be filed before bank financing is approved, or after bank financing has concluded. The 109 families already displaced from their land and livelihoods from the proposed coal power plant in Lamu is a reminder that negative impacts happen well outside of this limited timeline. Many IAMs have eligibility criteria that preclude communities facing harm from accessing redress through the IAM process. These timeline criteria demonstrate the continuing barriers communities face when seeking recourse.

Console benchmark report of eligibility criteria across IAMs

A further 79 complaints failed to pass eligibility because “inadequate information was provided” or because of the “good faith” requirement that complainants exhaust other alternatives before filing a complaint. These ineligibility criteria in particular highlight the onerous conditions that communities are sometimes required to grapple with; as communities may not be aware what additional information is needed in preliminary complaint stages, and “good faith” negotiations with other parties may not be possible when precluded by power dynamics, cultural barriers, or threats of violence. These issues are hard to mitigate without greater reporting transparency, as it is difficult to assess precisely which information was missing, or whether the good faith requirement was a reasonable expectation in particular circumstances.

Eligibility processes can serve an important function; many complaints fall well outside the scope of an accountability mechanism’s mandate, and should be redirected at the earliest possible stage to the appropriate bodies. But many other complainants simply fail to navigate the complex procedures sometimes required to meaningfully engage with IAMs. Better transparency on eligibility outputs, and simpler eligibility criteria, would go a long way in ensuring registration and eligibility processes are being conducted fairly, justly, and effectively.

This article was originally published in the Accountability Console Newsletter, where AC’s Research team shares research and insights from the world’s most comprehensive database of Independent Accountability Mechanism (IAM) complaints, the Accountability Console. Click here if you would like to subscribe to the monthly Console Newsletter.