Fast-Tracked COVID-19 Financing Requires Communities’ Expertise To Succeed

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) are responding to the COVID-19 pandemic by providing financial support at unprecedented levels and speed. MDBs have approved over USD 58 billion for emergency COVID-19 response in the last month alone,1 and that is just the beginning. The World Bank Group is already preparing to deploy as much as USD 160 billion in commitments over the next 15 months with the hopes of shortening the time for global economic recovery and “build[ing] conditions for broad-based and sustainable growth.”

The need for financial support during this crisis is both immense and acute, and without a doubt, MDBs should rise to the challenge. The urgency of this moment means that every dollar of financing needs to deliver its intended impact; there is no room for unintended consequences.

What is frightening then is that the risk of unintended harm is even greater when decisions are made and implemented quickly, because there is simply less time – and sometimes less will – to incorporate local communities’ expertise and conduct thorough social and environmental due diligence. Communities impacted by bank financing are best positioned to understand whether the money is truly mitigating harms caused by the pandemic because they are the very people the financing is intended to help, and they suffer the most if it does not.

As the pandemic heightens threats to vulnerable communities, it is critical that MDBs take the steps needed to ensure they put these communities at the very center of the financing decisions.

How Fast-Tracked Aid Risks Sidelining Communities’ Expertise and Why it Matters

Although MDBs have environmental and social safeguards that apply to all of their financing, whether fast-tracked or not, the fast-tracked nature makes it more difficult to adequately engage with communities and, as a consequence, to ensure adherence. Two aspects of COVID-19 financing make it particularly difficult for communities to engage: (1) banks may limit community consultation processes in time and scope; and (2) banks are lending more to financial intermediaries, which reduces the transparency of projects and who is responsible for them.

Risk #1: Limited consultation will prevent MDBs from hearing vital community feedback on project impacts.

Coronavirus poses a particular challenge for consultation with communities. Not only are projects being fast-tracked, thus limiting the time and scope that MDBs are likely to dedicate to consultation, but the in-person convenings that are best-practice for effective consultation are dangerous in the context of a pandemic.

Source: Accountability Console

Consultations with local communities are a core component of social and environmental due diligence – and for good reason. These consultations are essential for MDBs to ensure that they have context-specific understanding to prevent and mitigate adverse impacts of investments. In addition to soliciting direct local knowledge, consultations help build trust between project stakeholders, provide communities with the opportunity to object to a project, and facilitate access to key project information, such as project plans, potential impacts, and forums available for affected communities to raise concerns.

Despite their importance (and mandated nature), consultations with affected communities are often inadequate, even when financing is not fast-tracked. Take for instance communities we represent in Myanmar, who were not adequately consulted on a conservation project meant to protect 1.4 million hectares of biodiverse forest and coastal ecosystems. It turns out that the communities were aware that the project design ultimately risked increased deforestation – the very thing the financing was intended to prevent – as well as human rights violations and threats to the region’s fragile peace.

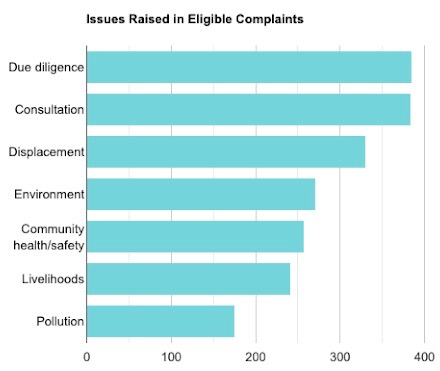

In fact, out of all eligible complaints filed to independent accountability offices tied to international financial institutions, communities have cited inadequate consultation and lack of due diligence substantially more than any other major issue raised.

If communities are not provided with adequate notice of investment activities and an opportunity to provide input, then they will have practically no ability to warn MDBs of potential harm and guide more prudent implementation – risking disastrous results.

Risk #2: Communities’ access to information and engagement are further restricted due to reliance on financial intermediaries.

In addition to the risk that inadequate consultation reduces access to information, there is another threat to transparency that implicates communities’ ability to provide feedback on the impact of COVID-19 financing: MDBs’ use of financial intermediaries. Many of the COVID-19 packages offered by MDBs do not go directly from the banks to their final recipients. Instead, MDBs will direct funds to local banks and other investors, often referred to as financial intermediaries (FIs), who will then finance projects. For instance, billions of dollars from the International Finance Corporation (IFC) will go to such client financial institutions, notwithstanding leadership’s prior acknowledgement of the environmental and social risks posed by FIs.

While the use of financial intermediaries may have benefits, including localizing finance decisions and increasing the speed at which financing can occur, it also obscures the investment chain – resulting in a harmful lack of transparency. Further, many FIs do not have comparable social and environmental protections or accountability to those the MDBs require. Although these safeguards are supposed to pass down to the FIs as well as project implementers, when the link to an MDB is rendered invisible by use of an FI, communities’ ability to know those safeguards exist – and hold investors to them – is severely restricted.

Marine biodiversity and traditional livelihoods are threatened by the Lamu coal plant

The Lamu coal-fired power plant in Kenya is an example of how difficult it is to ascertain whether an MDB is involved in a project financed through intermediaries. Despite a 2013 pledge to fund coal plants only in “rare” circumstances, the World Bank has continued to support coal indirectly by providing funds to FIs who then finance coal plants, including in Lamu, Kenya. Fisherfolk and farmers whose livelihoods, health, and climate are jeopardized by the Lamu coal plant sought accountability. It took thorough investigation by community-based organizations and international NGOs to uncover the multiple financing sources, including financial intermediaries who received investments from the private-sector arm of the World Bank, the International Finance Corporation. Among the impediments to information, the IFC’s investment in a South African bank was never explicitly disclosed in the IFC’s project information portal, and the IFC did not disclose the financial intermediaries’ sub-projects. As a result, a number of financial connections between the IFC’s financial intermediaries and project implementers and their shareholders had expired before the communities’ complaint was filed. Once the intermediaries had completed their financing, a complaint to the IFC’s accountability office became ineligible, a technicality that permitted the IFC to escape accountability in this case – putting local communities and the environment at risk and undermining the World Bank’s own climate goals.

Therefore, when financial intermediaries are involved, it is increasingly difficult for MDBs to ensure that their financing is being used for its intended impact and that it is environmentally and socially responsible. If financial intermediaries are not adhering to the MDB’s safeguards and communities do not know an MDB is involved, how could MDBs expect to learn about unintended impacts of projects?

Recommendations to Ensure that COVID-19 Financing Benefits from Communities’ Expertise

The way to mitigate the risk that MDBs do not hear from communities about billions of dollars of COVID-19 financing is in a sense quite simple: MDBs need to increase their engagement with communities. At a minimum, MDBs should take the following steps to ensure their COVID-19 response does not result in unintended harm:

- MDBs should not take for granted that communities will know that environmental and social safeguards exist to ensure that financing does not cause harm. All MDBs should issue official statements clarifying that all of their existing environmental and social safeguard policies apply to all financing in response to COVID-19.

- Just as many communities do not know that protections exist, they also do not know that MDBs have mechanisms for responding to allegations of harm. In this regard, all MDBs should state publicly that their existing accountability offices have the ability to receive complaints related to impacts of all financing in response to COVID-19.

- MDBs should recognize that it is difficult for communities to know whether MDBs financed a specific project or not. To address this, MDBs should include all financing decisions and corresponding documents for projects receiving COVID-19 fast-tracked funding on their websites and update this information regularly. This information should be shared in languages relevant to the projects to ensure it is accessible to affected communities.

- However, not all communities will know, or be able, to check MDBs’ websites for updated project information. MDBs can ensure that those communities are aware of their involvement by requiring all recipients of financing – including borrowers, financial intermediaries, and project implementers – to publish not only online but also at project which MDB(s) provided the financing, the corresponding safeguard policies that apply, and the accountability offices available to address community concerns.

- Finally, MDBs need to consider how to address the impact that restrictions on travel and gatherings have on consultations. The fact of the matter is that nothing is an adequate substitute for in-person consultations with communities. MDBs should consider what remote communication options exist and engage with them not only once but regularly and throughout the lifetime of the financing. MDBs could ask the same of their financing recipients and require reports on the outcomes of those engagements. Even when difficult, MDBs should prioritize ensuring that communities are aware of potential project impacts and have the opportunity to convey concerns and recommendations.

Responding to a crisis is the exact time when multilateral development banks should want to ensure that their money is hitting its intended mark. If community awareness and engagement is limited, banks will lose their most critical tool in understanding the impact of their financing, and their ability to prevent unintended harm will be greatly diminished. If MDBs do not mitigate potential harm from fast-tracked finance by providing adequate information to communities and listening to their feedback now, then they should be prepared to answer for the damage down the line.

—

1 On March 17, 2020 the WBG approved a financial package that provides the International Finance Corporation with USD 8 billion in fast-tracked financing to private companies, and provides the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the International Development Association with USD 6 billion to support health care initiatives. Within three weeks, the WBG approved the first group of fast-tracked projects, deploying USD 1.9 billion for new projects in 25 different developing countries, and USD 1.7 billion for emergency components of existing projects.

Similarly, the Asian Development Bank announced that it will deploy USD 6.5 billion to meet the immediate needs of member states grappling with COVID-19, and it is poised to provide additional financial assistance. The Inter-American Development Bank Group announced priority support areas for countries affected by COVID-19, and the African Development Bank approved a USD 3 billion “fight COVID-19 social bond,” the largest ever social bond in capital markets, to provide significant rapid support to member countries. Similar financial packages have also been offered by the EBRD and the AIIB, to name a few.